Conclusion and Recommendations

Flood-induced chemical disasters pose a serious and underappreciated risk to the most vulnerable communities throughout Virginia, and state and local governments are not prepared for toxic floodwaters.

Virginia lawmakers and regulators have not effectively responded to the threat posed by flooding of industrial sites resulting in hazardous contamination within nearby communities.

Without urgent and meaningful response to this threat, Virginia is vulnerable to community-wide contamination incidents of the type recently observed in Texas and North Carolina. Plant operators will continue to operate in increasingly flood-exposed sites without taking steps to prevent toxic floodwaters. If flooding occurs, weeks and months will pass before contamination can be thoroughly identified and remediated, which will be too late for affected communities to receive the resources they need to protect their health and property. Therefore, Virginia lawmakers and regulators must act with urgency today to address pollution control at flood-exposed industrial facilities and prepare for additional reform as climate change increasingly floods parts of the Commonwealth.

In short, while we may not be able to prevent flooding, as climate change advances, policymakers will face an imperative: require that facilities that use or store toxic and hazardous chemicals be hardened to prevent discharges in the case of severe flooding, or more simply, require that hazardous substances be removed from the path of likely floodwaters. This is a difficult task, given the sheer quantity of facilities that pose a threat, but ignoring the problem will threaten lives, livelihoods, and entire communities.

We recommend that Virginia’s elected officials, policymakers, and regulators examine the risks from toxic floodwaters and take steps to reduce the threat. State and local governments, in collaboration with community partners, should also dedicate meaningful resources to support those communities that bear the greatest risk of harm from toxic floodwaters.

Officials have shown this is possible, as Virginia is already starting to respond to certain climate-related threats. Last year, the Commonwealth’s political leadership launched new efforts to implement adaptation strategies.[i] The efforts are intended to promote flood and climate resilience. For example, agencies are beginning to develop a Virginia Coastal Resilience Master Plan and set construction standards for state facilities. The Governor has appointed a cabinet-level Chief Resilience Officer for the Commonwealth to lead the multi-agency directive. These efforts are an important first step, but they do not match the scale of Virginia’s climate adaptation challenge, and none of them focus specifically on the regulatory reforms necessary to address chemical-related risks from industrial sources.

RECOMMENDATION: Use existing legal authority to prevent climate-driven chemical disasters.

State regulators and their partners should develop a statewide, comprehensive analysis of the climate vulnerability of industrial facilities, and they should conduct a risk assessment for chemical disasters and climate-driven pollution. The analysis should consider all areas of the Commonwealth and should prioritize 1) facilities with high levels of potential flood exposure and 2) facilities in socially vulnerable communities.

State and local regulators should also evaluate how existing laws could be used to prevent toxic floodwaters. Under existing legal authority, regulators could force facilities to consider future risks for site flooding from extreme weather and sea-level rise. If flooding risks are present, they should be noted and addressed in spill contingency plans or stormwater pollution prevention plans. State regulators could also take steps to prevent flood-induced spills without new rulemakings or legislation. For example, regulators could issue new guidance to industry for how to implement spill prevention and control practices that consider climate vulnerability.

Regulators should also target enforcement against those facilities, located in flood-prone environmental justice communities, that are discharging above permitted levels or failing to develop required pollution prevention plans. To this end, DEQ should realign its enforcement policy and invest new resources to prioritize inspection and enforcement efforts on flood-exposed facilities located near the Commonwealth’s most socially vulnerable communities.

RECOMMENDATION: Improve public access to data about potential chemical hazards.

The Virginia DEQ and the Virginia Emergency Response Council should provide public access to facility reporting data pursuant to the Virginia Freedom of Information Act and the federal Emergency Planning and Community-Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA). Congress enacted EPCRA in the wake of the 1984 chemical plant explosion in Bhopal, India, which killed at least 3,700 and injured more than half a million. EPCRA was, however, years in the making, arising from coordinated state-level advocacy by labor and environmental advocates that drove change nationally. In EPCRA, Congress enshrined a right to information about the hazards that polluting industry had once foisted on the public without our knowledge. But EPCRA’s promise, and Congress’ intent, has been undermined in many states. In Virginia, communities have not been given access to some EPCRA information.

Illinois Makes Tier II Data Freely Accessible to PublicIllinois’ Emergency Management Agency provides publicly accessible and searchable databases for Tier II facility reporting data, including facilities that use and store hazardous chemicals and extremely hazardous substances, as well as facility reports for incidents involving hazardous materials. |

In particular, EPCRA requires disclosure of so-called Tier II facility reporting data to the public to alert communities about risks when a company is storing certain chemicals and so-called “extremely hazardous substances.” The law also requires disclosure by state regulators to local government and emergency responders in order to promote safe and effective disaster response planning. The chemicals subject to reporting include heavy metals, corrosive acids, toxic ammonia, and petroleum products. EPCRA also requires annual reporting of releases of toxic chemicals to the air, water, and land (the so-called Toxics Release Inventory). While DEQ makes the release data easily available on its website, it has not disclosed the data on the chemicals being stored at industrial facilities, which is far more relevant for the toxic floodwaters scenarios discussed in this report.

Many flood-exposed facilities that store hazardous chemicals, such as warehouses and retail facilities, are likely not regulated under any other federal or state pollution control program. EPCRA is therefore the only law through which the public can know about the hazards in their communities. DEQ disclosed Tier II data to citizens in earlier reporting years but more recently has restricted access, a regressive development for the Commonwealth. We used this earlier data in our facility flood-exposure analysis. [ii]

DEQ should immediately reverse its recent policy on public disclosures of Tier II data and should make this hazardous chemical storage data freely accessible to residents through online access, as other states, such as Illinois, have already done.[iii] The agency should also take steps to ensure appropriate use of this open information by providing context and interpretation to help residents understand the risks that go along with storage of hazardous chemicals and extremely hazardous substances in their communities. DEQ’s decision to withhold this data from the public raises serious questions about whether the agency is effectively utilizing this data for its regulatory purposes. DEQ should clarify whether Tier II chemical storage data are being actively shared with first responders and emergency planners, like local firefighters and local emergency planning councils, as EPCRA requires. The agency should also consider whether the Tier II reporting data can be used by regulators to promote reduction in the use of certain hazardous chemicals. Critically, DEQ should devote enforcement resources and coordinate with EPA, as necessary, to ensure rigorous compliance by what is likely a large number of diverse facilities subject to Tier II reporting requirements.

RECOMMENDATION: Establish new requirements for unregulated chemical storage tanks.

Virginia lawmakers and regulators should work together to establish a comprehensive regulatory regime for aboveground chemical storage tanks. The new program should reflect Virginia’s established regulatory program for tanks storing petroleum projects and certain hazardous substances. Currently, there are no siting, construction, monitoring, or spill-prevention standards in place for most aboveground chemical storage tanks.

Massachusetts Is Working to Prevent Toxic FloodwatersIn Massachusetts, the Office of Technical Assistance (OTA) works with flood-exposed businesses to identify and reduce the use of toxic chemicals. Through its “Chemical Safety and Climate Change Preparedness” initiative, OTA has mapped EPCRA Tier II reporting facilities, CWA permitted facilities, and underground storage tanks, among other industrial facilities vulnerable to inundation from hurricane storm surge, sea-level rise, and river flooding events. OTA deploys technical guidance, training, and direct assistance to local government, first responders, and emergency planning councils to help raise awareness about the threat of storm-induced chemical disasters. OTA also assists in integrating this information into local emergency plans and preparedness programs. Finally, OTA provides free and confidential consultations with affected businesses to identify toxic chemicals and develop plans for reduction in toxic chemical use or adoption of less toxic alternatives. Massachusetts produced the type of analysis that we have presented in this report, while also committing substantial resources to use the data to better protect at-risk communities by reducing vulnerability at flood-exposed facilities. Virginia should follow Massachusetts' lead. |

In 2014, a chemical spill occurred at the Freedom Industries chemical storage facility on the Elk River near Charleston, West Virginia. Thousands of gallons of a toxic chemical used for cleaning coal were found to have leaked into the river from an unregulated aboveground storage tank. Some 300,000 residents in and around Charleston were without access to drinking water. West Virginia lawmakers responded by passing new reporting and regulatory requirements for aboveground chemical storage tanks. As of 2016, West Virginia regulated nearly 42,000 aboveground chemical storage tanks, of which more than a quarter are over 30 years old and, in some cases, older than 75 years.[iv]

A new program in Virginia should be responsive to present and future flood risks. For example, regulations for new chemical storage tanks should require siting and construction standards to prevent or limit flood risk, including, for example, standards for elevation of tanks. We recommend that all new chemical and oil storage tanks in flood-exposed areas be elevated at least four feet above the ground to minimize risk from floods and storm surge. Like Virginia’s program for petroleum storage tanks, state regulations should require leak monitoring devices and secondary containment mechanisms for all new tanks and for existing tanks within a certain time period. Finally, the program should also set maximum age limits for tanks and require regular inspections and maintenance measures to ensure that no spills will be caused by degraded storage tanks.

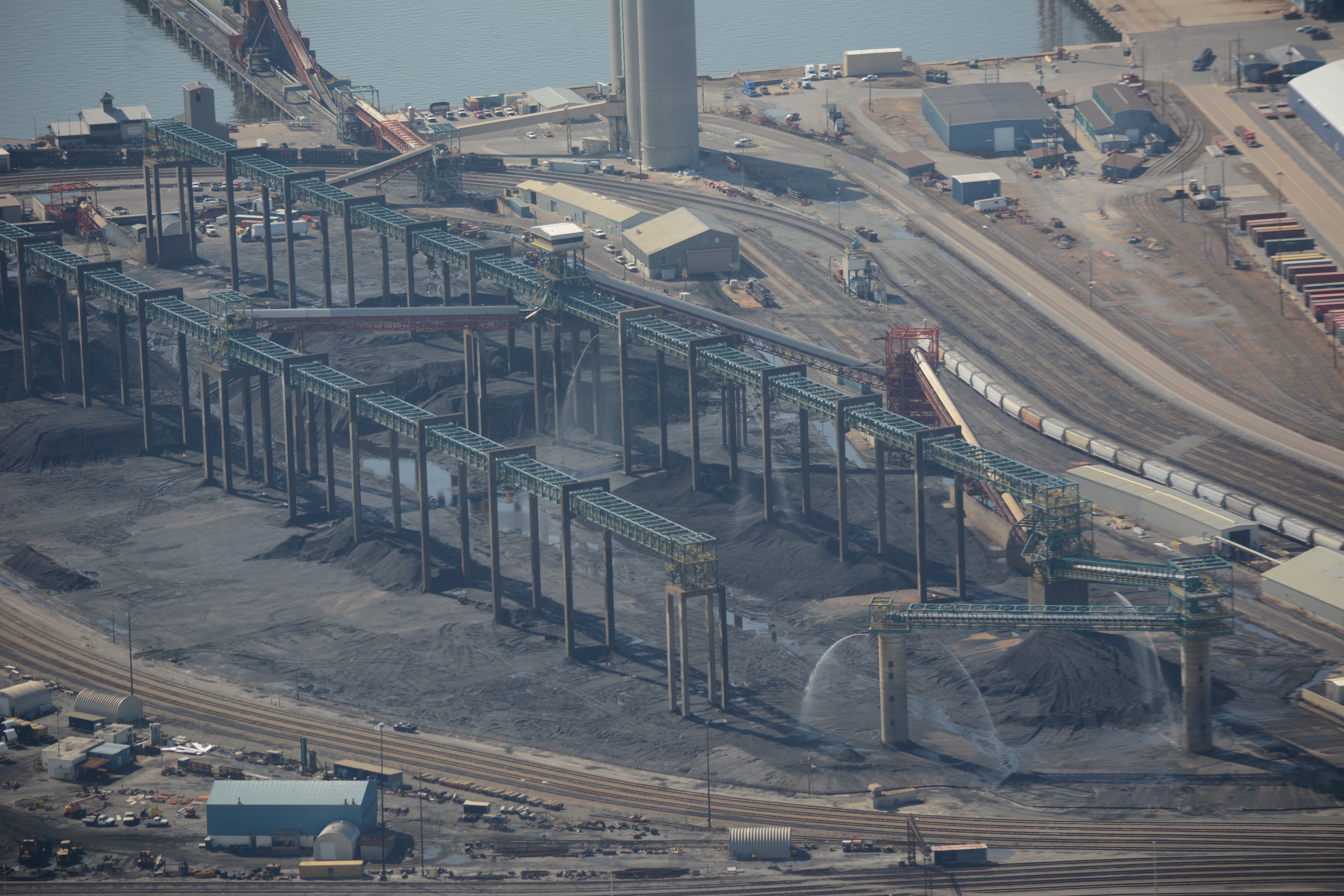

RECOMMENDATION: Ensure removal and containment of coal ash waste into landfills that are not flood-exposed, under present-day or future climate conditions.

Millions of tons of toxic coal ash are stored in unlined pits along rivers in Virginia, including the James River and its tributary the Elizabeth River. Monitoring of groundwater and surface water near these facilities has confirmed that toxic chemicals, like arsenic and cadmium, are already leaking from these sites during normal, dry-weather conditions into streams, rivers, and drinking water wells. These sites are also exposed to flooding from rivers and hurricane storm surge, which will only be further exacerbated by future sea-level rise. Thousands of people are living in census tracts that scored moderate to the highest level of social vulnerability and that are located adjacent to and downstream of these coal ash pits.

In February 2019, the Virginia General Assembly enacted legislation that strengthens the weak Federal Coal Ash rules, which allow utilities to close coal ash impoundments in place. If the coal ash is left in place for decades, there is a substantial risk of flood-induced spills and resulting toxic contamination similar to incidents recently observed in North Carolina during Hurricane Florence. Construction of new coal ash landfills in these highly vulnerable areas would not meet EPA criteria, yet current federal regulations allow utilities to leave decades old coal ash impoundments in place.

The recent Virginia legislation requires Dominion Energy to remove hazardous coal ash from several uncontrolled, riverfront storage pits throughout the Commonwealth, including three within the James River watershed. The law requires disposal and containment of the coal ash waste into new or existing landfill facilities, which are required to comply with state regulations on solid waste disposal.[v] However, only new landfills are bound by a state regulatory prohibition on siting within the 100-year floodplain or "base flood."[vi] The coal ash legislation and state regulations do not prohibit disposal into landfills, new or existing, that are exposed to flooding from 500-year storm events, hurricane storm surge, or future sea-level rise. In other words, even under the new legislation, Dominion could excavate coal ash from its existing pits and dump it into newly constructed landfills that are still flood-exposed.

Virginia regulators should ensure that Dominion selects new or existing landfills for disposal of coal ash waste that are not presently flood-exposed or likely to become flood-exposed in the future. To this end, regulators should consider reforming state regulations on solid waste disposal to address flood exposure and climate vulnerability at new and existing landfills.

RECOMMENDATION: Establish a toxic floodwaters task force to investigate and recommend policy reforms.

While leveraging existing legal authorities to address toxic floodwaters is a critical first step, substantial regulatory reforms are urgently needed to reduce the growing threat of climate-driven industrial pollution in Virginia. The Governor and the General Assembly should commission a task force to broadly investigate ways to improve state pollution permitting, regulatory design, and disaster policy to address climate-driven chemical disaster.

The task force should meaningfully engage public and private partners and be comprised of key stakeholders, including government agencies, members of affected communities and community-based nonprofit organizations, and the philanthropic and business sectors. The commission should also leverage expertise by aligning its work with other state and local commissions, planning districts, and workgroups focused on climate change, environmental justice, disaster management, and adaptation. Virginia’s philanthropic community should support meaningful and enduring participation by key stakeholders through grant-making to community-based groups that have local expertise and work on behalf of communities vulnerable to toxic floodwaters.

The task force should undertake its own investigation of facility site exposure to present-day flood risks and future flood impacts from sea-level rise. The study should not be limited by the geographic or regulatory scope of this report but rather include facilities throughout the Commonwealth and those regulated by all of the relevant state and federal pollution control programs. The task force should document the particular site conditions at industrial facilities that may increase the likelihood of chemical releases during flood events. Finally, the task force should examine existing regulations to identify gaps in spill prevention and response. The task force should prioritize opportunities to move facilities away from flood-prone areas or reduce risks through on-site flood and pollution control practices.

Climate-driven chemical disasters may not be preventable in every circumstance, but the harms may be reduced. Pre-disaster planning is crucial. To this end, the task force should investigate whether local emergency planning councils and first responders have adequate resources and effective strategies in place. The task force should also examine whether the most vulnerable populations and communities have access to emergency transportation, housing, health care, and other services.

Pre-planning for long-term recovery can be equally as important as mitigation and response planning. Therefore, the task force should investigate whether Virginia has adequate resources to ensure timely testing and remediation of chemical spills.

[i] Va. Exec. Order No. 24 (Nov. 2., 2018) “Increasing Virginia’s Resilience to Sea Level Rise and Natural Hazards.” https://www.governor.virginia.gov/media/governorvirginiagov/executive-actions/ED-24-Increasing-Virginias-Resilience-To-Sea-Level-Rise-And-Natural-Hazards.pdf

[ii] Illinois Emergency Management Administration. Search for Tier II Facilities with 302 Reports. Retrieved from https://public.iema.state.il.us/FOIAHazmatSearch/TII302search.aspx; Illinois Emergency Management Administration. Search for Tier II Facilities with Hazardous Chemicals. Retrieved from https://public.iema.state.il.us/FOIAHazmatSearch/T2Search.aspx; Illinois Emergency Management Administration. Search for Hazardous Materials Incident Reports. Retrieved from https://public.iema.state.il.us/FOIAHazMatSearch/.

[iii] Amanda Frank and Sean Moulton. Chemical Hazards in Your Backyard. Center for Effective Government, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.foreffectivegov.org/chemical-hazards-your-backyard.

[iv] West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection. AST Registration Graphical Information. Retrieved from https://dep.wv.gov/WWE/ee/tanks/abovegroundstoragetanks/Pages/ASTRegistrationGraphicalInformation.aspx.

[v] 9 VAC 20-81.

[vi] See 9 VAC 20-81-120. Siting Requirements.