Guide for Citizen Action

In every community, leaders and dedicated advocates fight daily for their neighbors’ safety, health, and prosperity. Environmental laws are a vital tool in that fight, and government agencies such as the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) are accountable for ensuring that these laws work as intended. Many environmental laws have "citizen suit" provisions or other opportunities for judicial review that allow communities to hold polluters and government agencies accountable for their actions (or inaction in some cases).

In this section of the report, we provide a citizens’ guide to the major environmental laws. The seven programs summarized below are the best place to start looking for levers to reduce risks from toxic floodwaters and promote community resilience.

Mapping Toxic Hazards in the James River Watershed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

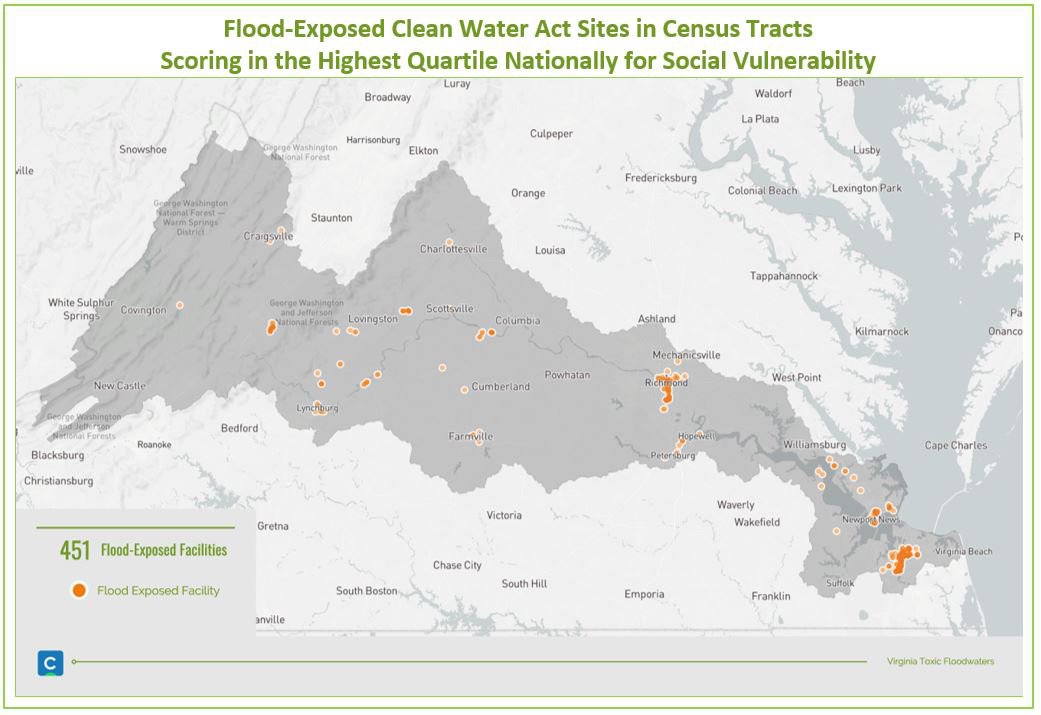

Clean Water Act

The Clean Water Act (CWA) is the major law protecting Virginia’s waters through regulation of entities that discharge pollution to waterways. The U.S. EPA has delegated authority to the Commonwealth to implement the CWA, and the Virginia DEQ is in charge of issuing pollution permits to dischargers and enforcing planning and pollution control requirements. State regulators can use the CWA and the state water laws to address climate-induced chemical spills. They should, for example, strengthen requirements for planning, site design, and spill prevention.

In the James River watershed, we identified a total of 1,112 facilities with state CWA pollution permits and/or required CWA pollution prevention plans that are located within 125 census tracts that score in the highest quartile nationally for social vulnerability to disaster. Of this number, we found 458 facilities that are flood-exposed.

In addition to pollution permits, which regulate wastewater discharges, most industrial facilities are also required to obtain permit coverage for stormwater discharges. These facilities must draft site-specific Storm Water Pollution Prevention Plans.

Under the CWA, facilities that store large quantities of oil (above 1,320 gallons) above or below ground must take measures to prevent, prepare for, and respond to accidental discharges of oil and must prepare a Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure (SPCC) plan. The largest oil storage facilities (above 1 million gallons) must prepare a more detailed Facility Response Plan (FRP) that includes planning for worst-case oil discharges.[1] Citizens can use the CWA to investigate the climate vulnerability of industrial facilities and to pressure regulators and facilities to address risks from climate-driven chemical spills:

- Citizens have access to required plans, such as SWPPP, SPCC, and FRP plans, and to compliance data. The plans and data are useful to determine whether facilities have considered potential flooding and whether accidental discharges, upsets, or other compliance issues are already problematic. State policymakers should improve access and interpretation of this information by vulnerable communities.

- The CWA includes public participation and citizen suit provisions that provide opportunities for the public to review, comment, and seek judicial review of pollution permits and the actions of government agencies. [2] Citizens may submit information and analysis through public comments that raise questions about whether a given permit is adequate in a flood-prone area. Citizen suits can also be used against facilities that violate requirements to prevent accidental releases.

- Citizens should demand timely and reliable public notification of accidental spill reports that CWA-permitted facilities file with state regulators. All CWA permittees are required to report unlawful discharges, including accidental spills or bypasses, within 24 hours.[3]

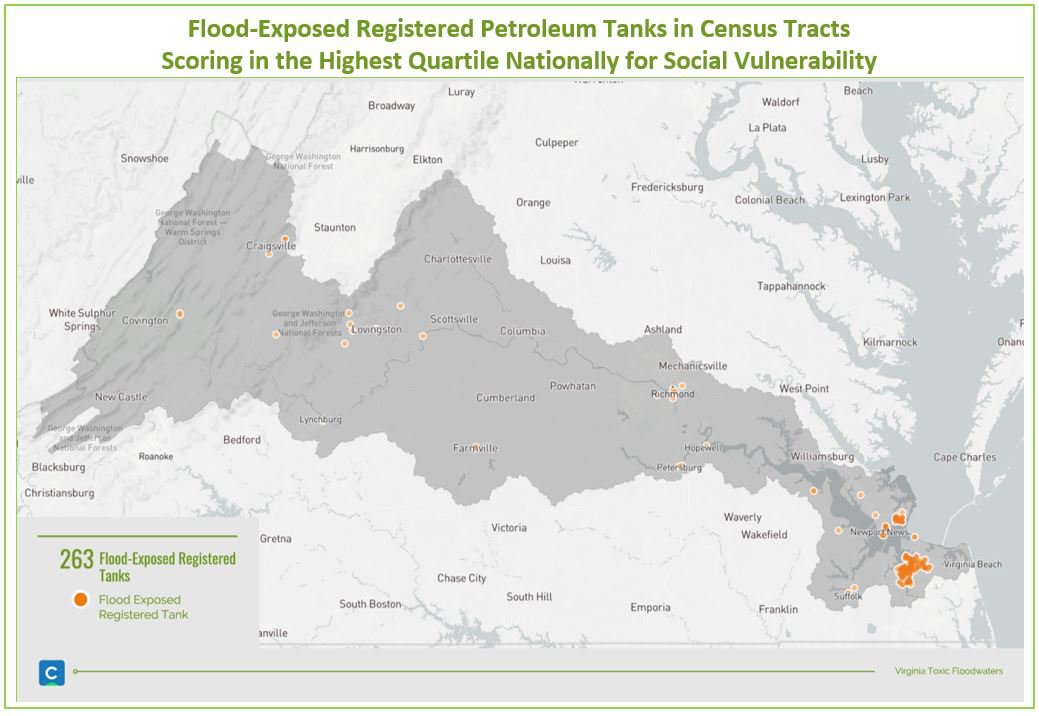

Virginia Registered Tank Program

The Virginia DEQ oversees implementation of federal and state regulatory controls for certain aboveground and underground petroleum storage tanks. As described in our recommendations, Virginia does not regulate most aboveground chemical storage tanks. In some cases, state-regulated petroleum tank facilities are also subject to federal regulatory controls, such as the CWA Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure (SPCC) and Facility Response Plan (FRP) rules.

In the James River watershed, we identified a total of 263 registered aboveground and underground petroleum tank facilities located within census tracts that score in the highest quartile nationally for social vulnerability to disaster. Remarkably, all 263 of these facilities are flood-exposed to varying degrees of river flooding, hurricane storm surge, and/or sea-level rise.

The regulations for aboveground petroleum tank facilities require certain pollution prevention practices, such as secondary containment for spills and corrosion protections.[4] Operators of aboveground petroleum storage facilities are also required to develop oil discharge contingency plans, which must be filed and approved by the State Water Control Board and updated every 60 months.[5] The required plan must contain assessments of natural resources and built infrastructure potentially exposed to oil spills. It must also assess consequences of the “worst case discharge,” defined as the total and instantaneous release of oil in the tanks during adverse weather conditions.[6]

Operators of underground petroleum storage tanks are required to install, maintain, and inspect certain spill prevention and containment practices, such as secondary containment, spill detection and alarms, and protections against corrosion.[7] Owners of these tanks must demonstrate financial responsibility for any potential corrective actions and liability for potential releases.[8] Operators must report and monitor suspected petroleum releases, investigate suspected off-site impacts, and must report, monitor, and remediate verified releases through development, approval, and implementation of a corrective action plan approved by the Board.[9]

Citizens have two key levers they can use to investigate climate vulnerability of petroleum storage tanks and to pressure regulators and facilities to address risks from climate-driven chemical disasters:

- For underground petroleum storage tanks, citizens are entitled to review, provide comment, and request a public hearing by the State Water Control Board to consider information related to spills and the facility operator’s proposed corrective action plan.[10]

- For aboveground petroleum storage tanks, citizens may submit freedom-of-information requests to DEQ for a facility’s contingency plans to determine whether operators have adequately considered climate and flooding impacts on the tanks. Citizens can also obtain each facility’s worst-case discharge assessments.

Risk Management Program

The Clean Air Act (CAA) is the principal federal program for controlling air pollution in Virginia, and under its terms the Commonwealth is delegated the authority to issue and enforce air pollution permits. The Risk Management Program (RMP), part of the CAA, requires permitted facilities containing certain hazardous chemicals in quantities exceeding established thresholds to implement risk management plans for accidental releases.[11]

In the James River watershed, we identified a total of 28 RMP facilities that are located within census tracts that score in the highest quartile nationally for social vulnerability to disaster. Of this number, we found five facilities that are flood-exposed. Hazardous and flammable chemicals such as chlorine, ammonia, oleum, and butane are among the most prevalent, in terms of location and quantity, at RMP-regulated facilities in Virginia.

RMP regulations require facilities to submit risk management plans and to update them every five years. These plans require analysis of potential worst-case scenarios, including, for example, the impact of potential flooding, as well as five-year accident histories, information about process and mitigation systems, and plans for coordination with local emergency response agencies.[12] The CAA’s General Duty Clause also requires facilities to prevent, minimize, and respond to accidental discharges of extremely hazardous substances.[13] Regulators evaluate facility hazards for several factors, including historic accidents, proximity to population centers, and requests from local governments and community groups. If regulators determine there is imminent and substantial endangerment to human health, they may order the facility to take steps to prevent threatened releases.[14]

There are a number of important opportunities and key levers that citizens can use to investigate climate vulnerability of industrial facilities regulated by the CAA and RMP and to pressure regulators and facilities to address the risks from climate-driven chemical spills:

- Citizens can read portions of facility’s risk management plans. However, the process is time-consuming and requires submission of formal requests and scheduling of an in-person review of documents at designated federal “reading rooms.”[15] The Right-to-Know Network and the Houston Chronicle have reviewed RMP plans for facilities nationwide and have made summaries available to the public online (http://www.rtk.net/).

- Like the CWA, the CAA includes public participation and citizen suit provisions, which may provide opportunities for the public to review, comment, and seek judicial review of permits that inadequately address climate impacts and permittees that violate requirements to prevent accidental releases.[16] During a permit proceeding, citizens may submit public comments that raise questions about whether a given RMP facility has adequately addressed projected climate and flooding impacts in its risk management plans and analyses.

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) is a federal regulatory program for managing the environmental and human health risks associated with hazardous wastes. In Virginia, regulators have been delegated authority to implement RCRA permitting and enforcement programs.

In the James River watershed, we identified a total of 1,193 RCRA-permitted facilities located within 125 census tracts that score in the highest quartile nationally for social vulnerability to disaster. Of this number, we found 335 facilities exposed to flood risks. The facilities include a variety of operations involved in the transport, storage, and disposal of hazardous waste. There are also facilities that generate thousands of pounds of hazardous and highly toxic waste per month and are required to have designated emergency coordinators and contingency plans for spills. Six of these flood-exposed RCRA facilities have been required to take corrective action to remediate historic site contamination.

RCRA permits impose standards for siting, design, and construction of facilities that are intended to prevent and mitigate unpermitted releases of hazardous materials.[17] The standards include criteria for flood protection only if the facility is located in a 100-year floodplain.[18] All RCRA permittees are also required to develop and implement plans for preparedness, contingency, emergency response, and for prevention of accidental releases.[19] The effectiveness of these pollution prevention requirements are, however, totally dependent on timely and technically thorough inspection and enforcement by regulators.

There are a number of important opportunities and key levers that citizens can use to investigate climate vulnerability of industrial facilities regulated by RCRA and to pressure regulators and facilities to address potential climate-driven chemical disasters:

- Citizens have a right to public records such as permit applications, regulatory inspection reports, and compliance data. These documents may reveal whether actions have been taken by the facility operator or imposed by regulators to address flood vulnerabilities.[20] DEQ should make this information available online and assist underserved and vulnerable communities in understanding the significance of the records and data.

- Citizens are also entitled to public review and comment on proposed RCRA permits, with a corresponding legal right to seek judicial review of legally deficient permits.[21] Citizens may submit information and analysis through public comments that raise questions about whether regulators have adequately addressed projected climate and flooding impacts in a given RCRA permit. For newly proposed facilities, citizens can demand that proposed siting and design address projected climate impacts.[22]

- Finally, RCRA permits citizens to file suit against regulated facilities in order to prevent unlawful discharges of hazardous materials that present an “imminent and substantial endangerment to health or the environment.”[23]

Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act

The Emergency Planning and Community-Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA) is a federal law focused on promoting interagency planning for and increased public transparency about storage of chemicals and accidental chemical releases. The law requires emergency planning and coordination between federal, state, and local governments to respond to potential chemical disasters.[25] EPCRA also requires reporting by so-called Tier II facilities that are storing hazardous chemicals, extremely hazardous substances, and petroleum products above certain threshold amounts.[26] Such facilities are required to report to Virginia DEQ, on an annual basis, the amount and name of hazardous substances that they are storing on site.

In the James River watershed, we identified a total of 158 companies reporting storage of hazardous chemicals at or above Tier II reporting thresholds that are located within census tracts that score in the highest quartile nationally for social vulnerability to disaster. Of this number, we found 36 facilities that are flood-exposed. These facilities, such as shipping terminals, chemical plants, and home improvement retailers, have reported that they have on site hazardous substances, such as acids, heavy metals, ammonia, and oil and gas products.

EPCRA provides at least one key lever that citizens can use to further investigate climate vulnerability of industrial facilities and to pressure regulators: Citizens are entitled to access and review Tier II reporting data for facilities that use or store hazardous chemicals and extremely hazardous substances. Virginia DEQ has restricted its disclosure, however. With this information, residents would be able to learn more about potential chemical hazards in their communities and use this information to advocate for state and local emergency planning that addresses the potential for flood risks at these facilities. For further discussion, refer to our recommendation about EPCRA Tier II data disclosure in our recommendations.

Virginia Environmental Groups File Lawsuit to Tackle Climate-Vunerable FacilityIn one case, environmental advocates in Virginia have already taken notice of the climate-driven threat of industrial pollution in the James River watershed. Dominion Energy owns and operates the Chesapeake Energy Center on the Elizabeth River, a tidal tributary of the James in Hampton Roads. The facility contains an impoundment of more than two million tons of coal ash waste. In 2016, the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC), on behalf of the Sierra Club, filed a lawsuit to challenge pollution flowing through groundwater from the coal ash pit to the Elizabeth River. At the time of the lawsuit, Dominion, under state solid waste permits, was planning to leave the coal ash waste in place indefinitely, which would allow discharge of pollutants like arsenic to the Elizabeth River. SELC and Sierra Club were supported in their lawsuit by university researchers, who prepared a detailed climate vulnerability assessment of the facility. In their report, they found that the coal ash waste is highly vulnerable to flood hazards given that the site is exposed to river flooding and Category 1 hurricane storm surge, while projected coastal erosion and sea-level rise will exacerbate groundwater contamination and flood risk in the coming decades. SELC and Sierra Club secured a federal court ruling requiring development of remediation plans for the site. It was the first trial court ruling in the nation about coal ash pits as a source of water pollution. The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals later ruled that the trial court had not interpreted the Clean Water Act correctly. At present, however, Dominion is planning for excavation of all the coal ash at the Chesapeake Energy Center due to legislation passed by the Virginia General Assembly (as described in our recommendations). |

Superfund

The federal Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, better known as the “Superfund” program, authorizes the investigation and remediation of legacy hazardous contamination at thousands of former industrial sites. Superfund sites are typically among the most contaminated by uncontrolled hazardous and toxic substances. While in many instances these facilities have already been remediated, contamination may remain on-site that is still vulnerable to flooding episodes despite controls put in place to limit exposure during normal circumstances.

In the James River watershed, we identified 19 facilities either currently or formerly regulated under Superfund that are located within census tracts that score in the highest quartile nationally for social vulnerability to disaster. Of this number, we found nine Superfund facilities that are exposed to potential flooding. These sites include a former foundry, a U.S. Navy ordnance storage facility, and a residential site where soil was contaminated by lead.

The Superfund process begins with a preliminary assessment for potential contamination of air, groundwater, and surface water and harm to public health. If sufficient potential for hazardous contamination and harm exists, the site is added to the National Priorities List, which triggers potential federal enforcement to impose financial liability on parties responsible for the legacy contamination, like the generators of the waste, and also opens access to federal Superfund resources for further study and eventual site remediation.[27] In the next phase, federal regulators produce a remedial investigation and feasibility study, select a preferred alternative for site remediation, and publish the draft cleanup plan for public review and comment.[28] The selected alternative must meet a number of criteria, including the long-term effectiveness and permanence of the remediation practice and whether the alternative adequately protects human health and the environment, both of which may be affected by the impacts of climate change.[29] Finally, EPA regulators are required to conduct reviews of the site cleanup at five-year intervals following implementation of the remedial action.

Superfund provides at least two key levers for citizens to pressure regulators to address the climate vulnerability of current and potential Superfund sites:

- Citizens are entitled to review and provide formal comment on proposed cleanup plans. However, the minimum 30-day comment period is very brief by comparison to the many months and years of investigation and study of alternatives. A longer period of community outreach, through EPA’s Community Involvement Program, provides opportunity for engagement, including citizen advisory groups and public meetings that track the entire cleanup process. In cases where cleanup proposals and actual remediation may have already been completed, citizens may review approved cleanup plans or delisted sites to determine whether flooding would be likely to spread hazardous contamination and harm human health or the environment.

- Citizens are also entitled to seek judicial review of EPA cleanup decisions that violate any Superfund regulatory requirement or standard.[30]

Virginia Voluntary Remediation Program

Virginia’s Voluntary Remediation Program (VRP) is a state regulatory program for the oversight of voluntary remediation of hazardous contamination at commercial and industrial sites for the purpose of brownfields redevelopment. Like the federal Superfund program, the VRP addresses the uncontrolled contamination of air, groundwater, surface water resources on the site, and the potential harm to human health.[31] Importantly, eligibility requirements prevent owners from participating in VRP if the remediation of hazardous site contamination is otherwise mandated by other state and federal law, including, for example, CWA, Superfund, RCRA, and Virginia hazardous waste and solid waste regulations.[32] Like Superfund facilities, VRP facilities may have already been remediated to state regulatory standards, but the contamination that remains on-site could still be vulnerable to flooding episodes even with approved containment controls in place.

In the James River watershed, we identified a total of 62 facilities either currently or formerly participating in VRP that are located within census tracts that score in the highest quartile nationally for social vulnerability to disaster. Of this number, we found 18 facilities that are flood-exposed. These sites include a former automotive assembly plant, dry cleaning facility, riverfront power plant, and a brewery.

New England Nonprofit Files Lawsuits to Tackle Climate Vulnerable FacilitiesIn two recent cases, the nonprofit Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) has filed RCRA and CWA lawsuits alleging certain facilities have failed to take action to address “imminent and substantial endangerment” arising from the facilities’ vulnerability to increased precipitation, storm surge, and sea-level rise.[37] In its cases against ExxonMobil Corp. and Shell Oil Products US, CLF has alleged that the operators of the oil and gas marine terminals in Everett, Massachusetts, and Providence, Rhode Island, have failed to address present-day risks of pollution discharges arising from increased precipitation and potential storm surge. CLF has also alleged that the companies have knowledge of site risks from climate impacts, included projected sea-level rise, but have failed to disclose this information to regulators or address the vulnerabilities at these facilities through, for example, required CWA pollution prevention plans. As of early 2019, both cases are still pending in court. |

After an applicant site meets the eligibility criteria and is enrolled in the program, the participant must develop and submit a number of reports to state regulators, including a site characterization report, a risk assessment, a remedial action plan, documentation of public notice, and a demonstration of completion.[33] The extent of remediation is determined in consultation with state regulators and falls into three categories: contamination consistent with background levels; contamination that meets regulatory standards for human health and environmental quality; or contamination based upon risk assessments that is less protective but considers restrictions on future land use.[34] The participant must provide public notice and comment for a minimum 30-day period and must respond to any citizen that submits a comment. The facility operator must then provide the comments and responses to state regulators.[35]

VRP provides at least one key lever that citizens can use to further investigate climate vulnerability of industrial facilities contaminated by hazardous substances and to pressure regulators and facilities to address potential climate-driven chemical disasters:

- Review and public comment on participant site reports, remedial action plans, and other required submissions. Citizens could petition to revoke or modify the Commonwealth-issued certificate of completion or its conditions, if, for example, the site owner’s risk assessment does not account for potential exposures arising from site flooding.[36]

[1] 40 CFR Part 112.

[2] 33 U.S.C. § 1365.

[3] 40 CFR §122.41(l)(6).

[4] 9 VAC 25-91-130. Pollution Prevention Standards and Procedures.; 9 VAC 25-91-140. Performance Standards for Aboveground Storage Tanks Newly Installed, Retrofitted, or Brought into Use.

[5] 9 VAC 25-91-170. Contingency Plan Requirements and Approval.

[6] Id.

[7] 9 VAC 25-580.

[8] 9 VAC 25-590-10 et seq.

[9] 9 VAC 25-580-190 - 280.

[10] 9 VAC 25-580-300.

[11] 40 CFR §68.150-195.

[12] 40 CFR §68.165-180.

[13] 42 U.S.C. § 7412(r)(1).

[14] 40 CFR §68.20-42; 42 U.S.C. § 7412(r)(9).

[15] U.S. EPA. Vulnerable Zone Indicator System. Available at https://www.epa.gov/rmp/forms/vulnerable-zone-indicator-system; U.S. EPA. Federal Reading Rooms for Risk Management Plans. Available at https://www.epa.gov/rmp/federal-reading-rooms-risk-management-plans-rmp.

[16] 42 U.S.C. § 7604; 40 CFR §70.4(b)(3)(x).

[17] 40 CFR Part 264.

[18] 40 CFR §264.18(b).

[19] 40 CFR §264.50.

[20] For example, during the Obama administration EPA regulators recommended incorporating analysis of climate change impacts into RCRA permitting. U.S. EPA, “Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response Climate Change Adaptation Implementation Plan, June 2014” available at https://www3.epa.gov/climatechange/Downloads/OSWER-climate-change-adaptation-plan.pdf (last accessed June 22, 2017).

[21] 40 CFR §124; 40 CFR §270.

[22] 40 CFR §270.32(b)(2).

[23] 42 U.S.C. § 6972(a)(1)(B).

[25] 42 U.S.C. §§ 11001-11003.

[26] 42 U.S.C. §§ 11021-11022.

[27] 42 U.S.C. § 9601.

[28] 40 C.F.R. § 300.430.

[29] 40 C.F.R. § 300.430(e)(9)-(f).

[30] 42 U.S.C. § 9659; 42 U.S.C. § 9613(h).

[31] 9 VAC 20-160-90. Remediation Levels.

[32] 9 VAC 20-160-30. Eligibility Criteria.

[33] 9 VAC 20-160-70. Work to Be Performed.

[34] 9 VAC 20-160-90. Remediation Levels.

[35] 9 VAC 20-160-120. Public Notice.

[36] 9 VAC 20-160-110(h). Certification of Satisfactory Completion of Remediation.

[37] Complaint, Conservation Law Foundation v. ExxonMobil Corp., 1:16-cv-11950-MLW (D. Mass. 2016); Climate Case Chart. Conservation Law Foundation, Inc. v. Shell Oil Products US. Retrieved from http://climatecasechart.com/case/5619/; Climate Case Chart. Conservation Law Foundation v. ExxonMobil Corp. Retrieved from http://climatecasechart.com/case/conservation-law-foundation-v-exxonmobil-corp.

© Center for Progressive Reform, 2019