Barack Obama's Path to Progress in 2015-16: Thirteen Essential Regulatory Actions [UPDATED]

Introduction

How will history judge the legacy of President Barack Obama? As he waited for his first inauguration, the newly elected president summoned presidential historians to his Senate office to help him conceive of a framework for that legacy, daring to dream about the unique and exceptional contribution he would make to the quality of life of most Americans. Six years later, despite significant achievements, several of the most important components of his stated agenda seem to be beyond his reach. But the President still has a lot he can do, as well as a significant amount of time left for these accomplishments. He won’t leave office for two years yet, and he wields enormous power over the myriad policy matters within the purview of the Executive Branch, unrestrained by congressional gridlock.

In his 2013 and 2014 State of the Union addresses, the President declared his intention to use his executive authority more aggressively, particularly in areas where Congress has demonstrated repeatedly that it will not act. The President has ample legal authority to pivot toward such affirmative steps, regardless of attempted congressional interference, and his determination to take such steps is both crucial and smart. The more policies and rules the President is able to get on the books now, the harder it will be for his opponents to unravel his contributions later.

In no area are the opportunities greater than with respect to protecting public health, safeguarding worker and consumer safety, and preserving the environment. Distracted by the increasingly hysterical drumbeat of conservative rhetoric about a supposed “tsunami” of regulations, the White House has barely scratched the surface of what regulatory actions could do to deliver on the promise made in the President’s second inaugural to “care for the vulnerable, and protect [our] people from life’s worst hazards.”

The American people are in dire need of such care, and federal agencies have already expended thousands of hours compiling the evidence needed to deliver them. What has been missing, and what needs now to come into play, is a sense of urgency and the political will—the President’s, in particular.

This Issue Alert identifies 13 essential regulatory actions that agencies are working on right now, all of which can and should be done before the President leaves office. These rules come out of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Department of Labor, and the Department of Transportation. All are now years overdue, particularly considering the very serious health, safety, and environmental effects they address. Each day, people get ill and too many die because earlier Administrations dragged their feet on these problems. If President Obama wants a legacy that delivers on the core domestic policy promises of that second inaugural address, he should carry these overdue proposals across the finish line, not at the very last minute but in time to avoid their further delay or potential undoing by a succeeding administration that may be hostile to protective safeguards.

Unfortunately, legacies are made real not by inspiring speeches but by concerted, well-organized, and hard-driving action, characteristics that, in the regulatory arena, have not been evident for many years. In fairness, when President Obama took office, the agencies we depend upon to protect the most vulnerable were already hobbled by eight long years of abuse and neglect during the George W. Bush Administration. Yet the Obama Administration has too often left them hanging, without the resources they need to accomplish their rule-writing and enforcement missions. The President has allowed White House political operatives to overrule his senior agency heads, presumably so as to avoid inflaming political opposition from industry. Now that the President’s last mid-term election has come and gone, a window of opportunity has opened, offering barely enough time to put new regulatory safeguards in place that will make it difficult for a new president to destroy these vital components of a lasting Obama legacy.

Because time is short and so much work remains to be done, we recommend that the President appoint a senior White House advisor to be the point person to organize and ride herd over the considerable effort that will be required to make these and other rules final by no later than June 30, 2016. That person should be someone who has plenty of White House experience, and whose voice will command the respect of the agencies and the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, which often serves as a choke point for regulations. We choose that June 2016 date because it effectively immunizes the rules from repeal by a new president under the time frames set forth in the Congressional Review Act, should the Republican Party take control of the White House and hold both houses of Congress in the following November elections.

The President should direct the affected agencies to assign whatever staff is necessary to drive these rules forward to conclusion. All should be elevated to the same status as the climate change rules: do or die priorities for the President. For many of these regulatory actions, Congress will attempt to attach “riders” to any legislation moving through both houses that are designed to prevent the Obama Administration from completing the rulemaking process. The riders might accomplish this goal by repealing necessary legal authority, instituting impossible-to-meet rulemaking requirements, or prohibiting an agency from using its appropriated funds for working on the rule. In every instance, the President must commit to vetoing any legislation that contains an antiregulatory rider that would block any of these actions.

The “Essential 13” regulatory actions highlighted in the pages that follow include:

- National performance standards to limit greenhouse gas emissions from fossil-fueled power plants. EPA rules that would reduce climate disrupting greenhouse gas emissions from new and existing fossil-fueled power plants by about 730 million metric tonnes, while annually preventing up to 6,600 premature deaths, 3,300 non-fatal heart attacks, 150,000 asthma attacks in children, and 490,000 missed school and work days by limiting other common air pollutants. The President has already committed to this rule, and so far it is on track, but along with the other actions explained here, the Administration should finish it in plenty of time, and not at the last possible minute.

- Preventive controls for processed foods. FDA rules that would seek to prevent catastrophic foodborne illness outbreaks, such as the recent Salmonella-tainted peanut butter outbreak that killed nine people and sickened at least 714 others, by requiring foods processors to proactively identify and address hazards in the manufacturing process.

- Produce safety. An FDA rule that would seek to prevent catastrophic foodborne illness outbreaks, such as the recent Listeria-tainted cantaloupe that killed 33 people and sickened at least 147 more, by establishing new minimum health and safety standards for farming practices that can cause produce contamination.

- Imported food safety. With imports making up 15 percent of the food consumed in the United States, and with fewer than 2 percent of imported foods undergoing inspection, these FDA rules would help to prevent catastrophic foodborne illness outbreaks by requiring U.S.-based importers and foreign-based suppliers to ensure their products are meeting the same high safety standards that apply to U.S.-based facilities.

- Silica standard. An OSHA rule to better protect the nearly 2 million U.S. workers exposed to dangerous levels of silica dust in the workplace that would require employers to implement silica dust controls, monitor their workers’ exposures, and provide improved employee training and medical surveillance.

- National ozone air pollution standard. An EPA rule that would annually prevent up to up to 12,000 premature deaths, 5,300 nonfatal heart attacks, 58,000 cases of aggravated asthma, and 2.5 million missed school and work days by reducing the maximum allowable amount of ozone air pollution.

- “Waters of the United States” regulatory definition. With wetlands and smaller water bodies providing habitat one-third of U.S. endangered or threatened species and supporting a seafood industry annually worth $15 billion, this EPA rule would ensure these waters are better protected by clarifying that they are covered by the Clean Water Act’s provisions.

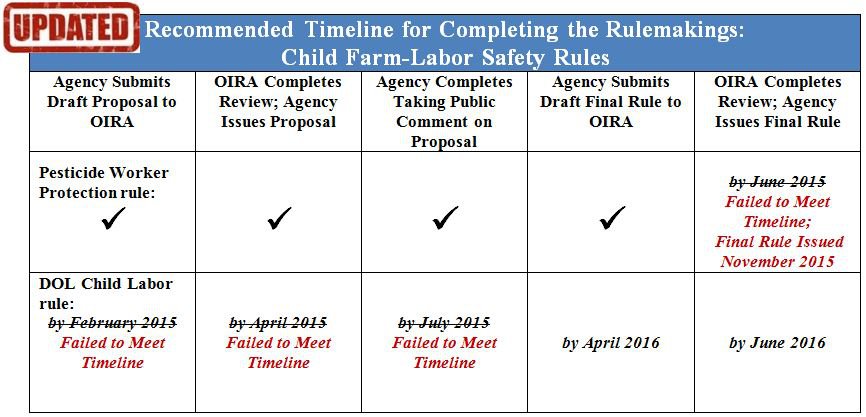

- Child farm-labor safety rules. To better protect vulnerable child agriculture workers, one of whom dies in a farming-related incident roughly every three days, these EPA and Department of Labor safeguards would prohibit children from taking on particularly dangerous farm work tasks and offer stronger protections against harmful pesticides.

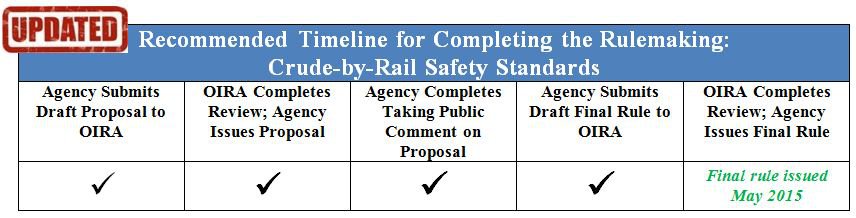

- Crude-by-rail safety standards. A Department of Transportation rule that would seek to prevent catastrophic train crashes involving any of the more than 415,000 rail-carloads of flammable crude oil traveling across the United States each year by requiring stronger tank cars, safer train routes for oil trains, and enhanced emergency response practices.

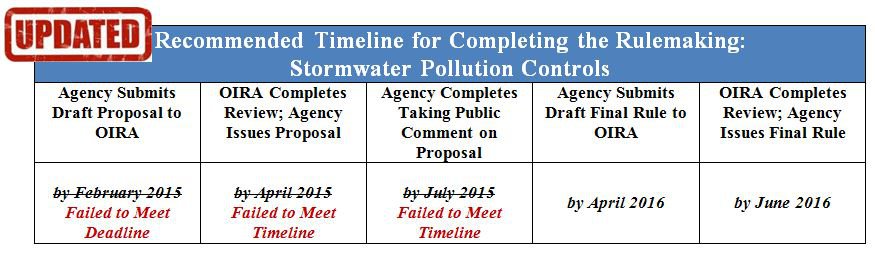

- National stormwater pollution controls. An EPA rule that would seek to prevent harm caused by polluted stormwater, which is responsible for nearly 11 percent of all impaired rivers and streams across the United States, by requiring municipalities and the owners of industrial sites to take steps to manage runoff that flows from their lands into nearby water bodies and by extending these requirements to a greater number of municipalities and covered industrial sites.

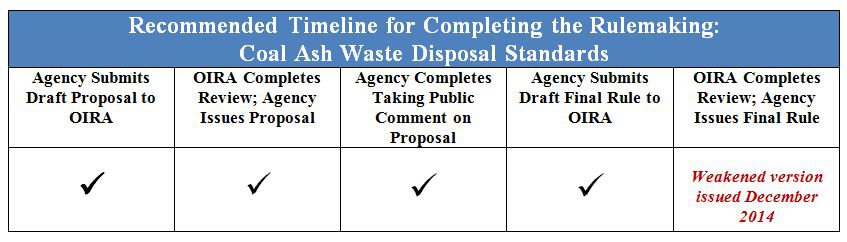

- Coal ash waste disposal standards. With most coal ash waste being dumped in old and poorly engineered impoundments across the country, this EPA rule would require power plants to better manage the more than 129 million tons of coal ash they produce annually in order to prevent contamination of adjacent ground and surface waters as well as catastrophic releases, such as the 1.1 billion-gallon coal ash spill in Kingston, Tennessee, which inundated 300 acres of land in a layer four to five feet deep, uprooted trees, destroyed three homes, and damaged dozens of others.

- Concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO) water pollution standards. With large-scale animal farms generating 500 million tons of manure each year, and with fewer than 43 percent of the facilities operating under Clean Water Act permits because of regulatory exemptions and insufficient state oversight, this EPA rule would better protect nearby water bodies from these operations by requiring them to follow necessary permitting requirements and adopt rigorous management practices for handling and storing their wastes.

- Permit “eReporting” for the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System. An EPA rule that would strengthen the agency’s ability to respond to water pollution violations and annually save states and regulated industries almost $30 million combined by requiring Clean Water Act permit holders to submit relevant reports in electronic—as opposed to paper—format.

To be clear, the choices of regulatory actions in this document reflect the reality that the Obama Administration has not seized the opportunity to challenge the fundamentally false assumptions that underlie the campaign to deregulate, except episodically and in the most rhetorical manner. This lack of vision has cost the President’s legacy and the American people dearly. So, for example, when conservatives shout that more rules have been produced by the Obama Administration than ever before, the White House counters with a set of tepid calculations that prove the meaningless fact that the Bush or Clinton Administrations made as many regulatory decisions. The White House apparently lacks the courage or the vision to explain that the rules that have been put in place will protect people and the environment from frightening harms. Because these benefits are never explained, because the issue is never really joined, the White House sacrifices the essential opportunity to explain why people need government and why protective regulations serve people and the economy, leaving some of the most important accomplishments of this presidency—most notably Obamacare—similarly lacking an organizing principle.

Because of these constraints and lack of vision, we find ourselves six years into the Obama Administration with a sharply constrained list of the possible. The best example is worker safety and health. Quite literally, President Obama could not have won the office without the strong support of organized labor, which no doubt lent its support in the expectation that the President would move aggressively in areas where his predecessor had not. And yet the possibility also exists that the Administration will close out eight years without producing a single important new rule to protect worker health and safety, instead waiting far too long to usher the lone contender—controls on silica dust—across the finish line. A far more ambitious agenda would have made both policy and political sense in 2009, but the passage of time has narrowed the horizon of possibility.

We can only hope that when he confronts this and similar instances of neglect, the President will deliver on his government’s power—as he said in his State of the Union speeches and on the campaign trail—to help people when they cannot help themselves.

This Issue Alert will examine each of the essential 13 regulatory actions individually, describing (1) why the regulatory actions are needed for protecting people and the environment, (2) the ongoing delays that have blocked their progress to this point, (3) what the final rules should say, and (4) the remaining steps that need to be taken to complete the rules. This examination will make clear that all of the rules will deliver important protections for public health, safety, and the environment and that completing the rules will be a relatively easy lift for the Obama Administration, provided that it brings to bear the necessary political will.

The Essential 13: Greenhouse Gases Rule

What's at Stake?

Scientists estimate that we’ve already locked in a 1.4-degree-Fahrenheit increase in average global temperatures since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, which is more than enough to create long-lasting, if not irreparable damage to the planet. September was the 355th consecutive month in which the global average temperature exceeded the 20th century average—a streak that has now reached nearly 30 years.[i] The average concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere exceeded 400 parts per million (ppm) every day in April, a level that hasn’t been reached in at least the 800,000 years.[ii]

We are already suffering the consequences of these drastic changes to Earth’s fragile atmosphere. Researchers estimate that the total area damaged by massive wildfires increased at a rate of 90,000 acres per year between 1984 and 2011, due in part to higher temperatures and worsening drought conditions brought about by global climate disruption.[iii] Researchers project that the annual total area of wildfire damage could increase by a further 100 percent by 2050, with just the climate change-induced wildfires alone costing the United States as much $60 billion every year by 2050.[iv] Over the last few years, large parts of the country have endured some of the worst droughts in decades, and scientists agree that the higher temperatures brought about by climate disruption have worsened their effects, including through massive declines in winter mountain snowpack—which are essential for sustaining rivers and reservoirs—and decreased soil moisture levels.[v] Researchers estimate that these drought effects will cost California farmers $2.2 billion and 17,100 jobs in 2014 alone.[vi]

Global average sea level has risen by eight inches since the 19th century, which is already wreaking havoc for Americans living in coastal areas. The beach at Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge in Virginia has been washing away at a rate of 10 to 20 feet every year,[vii] while Miami Beach, Florida has resorted to building a complex pumping system at a cost of $400 million to tackle the increasingly common floods the city faces.[viii] The rising air and sea temperatures are also aiding the spread of harmful invasive species, enabling them to displace native species and disrupt entire ecosystems across the United States and its surrounding waters. For example, the lionfish, normally a tropical species, has spread as far north as the North Carolina coast, destroying parts of the fragile Atlantic reef system along the way.[ix] Similarly, global climate disruption is enabling dangerous infectious diseases—such as Valley Fever and Naegleria fowleri, the so-called “brain-eating amoeba”—to expand throughout the United States.[x]

Things will likely get worse, even if the global community does somehow make good on the agreement it reached at the 2009 United Nations climate summit in Copenhagen to limit global temperature rise to the artificial target of 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit. More and more, climate experts agree that meeting this target will not achieve the global community’s stated goal of avoiding “dangerous” global climate disruption; they argue that the world has passed too many tipping points, making dangerous global climate disruption essentially a foregone conclusion. Instead, meeting the Copenhagen target may be what is necessary for avoiding “very dangerous” global climate disruption.[xi] But, we are not even close to being on the right path for meeting that target. The international accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers recently reported that the world is instead on course to see average global temperatures rise by 7.2 degrees Fahrenheit by 2100. The report also projects that at this rate the world will have exhausted its “carbon budget”—that is, the maximum amount of carbon dioxide emissions it can release before the end of the century—by the year 2034.[xii]

To have any hope of averting the most catastrophic effects of global climate disruption, the United States will need to significantly “decarbonize” its power sector—that is, we will need to minimize the country’s reliance on fossil-fueled power generation so that each unit of electricity that is produced results in drastically lower carbon dioxide pollution emissions. The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) pending national performance standards for both new and existing fossil-fueled power plants offers the most realistic opportunity for achieving this goal—especially in the face of continued Republican intransigence on enacting comprehensive legislation to address global climate disruption. Because fossil-fueled power plants are the largest single U.S. source of greenhouse emissions—accounting for nearly a third of all such emissions—these rules would go a long way toward promoting a greener economy.[xiii] Developing the technology to build a climate-friendly power sector would also create important economic opportunities, as the U.S.-based companies would be well positioned to export their innovations to markets in other countries working to tackle global climate disruption. By serving as a world leader, the United States would also enjoy greater diplomatic leverage to negotiate meaningful agreements with its international partners to ensure they are taking adequately ambitious steps to reduce their own greenhouse gas emissions.

As proposed, the EPA’s national performance standards for power plants would deliver significant public health and environmental benefits once fully implemented. The rules would reduce power plant emissions of carbon dioxide by about 730 million metric tonnes, which is roughly equivalent to the emissions produced by two-thirds of the country’s automobiles. As an important bonus, the agency also estimates that the rules would annually prevent up to 6,600 premature deaths, 3,300 non-fatal heart attacks, 150,000 asthma attacks in children, and 490,000 missed school and work days.[xiv] These critical public health co-benefits would be achieved as the rules would encourage greater reliance on clean energy sources, such as solar and wind, as a replacement for dirty coal-fired power plants, which are not only responsible for large amounts of greenhouse gas emissions, but also other air pollutants—including ozone and particulate matter—that are harmful to human health.

What’s the Holdup?

The EPA’s pending national performance standards to limit greenhouse gas emissions from fossil-fueled power plants have been met with intense opposition from a wide variety of business groups, including the coal mining industry and much of the power sector. These groups have already launched a series of specious lawsuits aimed at blocking the pending rules, despite the fact that longstanding administrative law principles generally forbid such legal challenges until after a rule has been finalized.[xv] Although the cases have little chance of succeeding on the merits and are procedurally flawed, these suits nonetheless serve as an intimidation tactic that industry can deploy to discourage the EPA from working as expeditiously as possible on the rules.

These industry groups have also worked with allied conservative think tanks and other outside influence groups to push anti-regulatory Members of Congress to oppose the rules. Their efforts have been rewarded with a series of bills that would block the specific rules or otherwise prevent the EPA from taking any actions to limit greenhouse gas emissions from power plants and other industrial sources.[xvi] They have also succeeded in attaching “policy riders” to must-pass appropriations bills that would prohibit the EPA from using any appropriated funds to support development of the pending national performance standards.[xvii] While many of these bills and policy riders have passed the Republican-controlled House of Representatives, so far none have cleared the Senate. Beyond these legislative actions, anti-regulatory Members of Congress have held several hearings aimed at undermining support for the EPA’s greenhouse gas rules. These hearings have provided these members and industry opponents with high profile opportunities to cite and recite their same fallacious talking points against the rules: the EPA lacks the legal authority to issue them; the rules would not make any meaningful contribution toward limiting greenhouse gases or yield any other public health or environmental benefits; and global climate disruption is a hoax.[xviii] Business groups and their conservative allies have also sought to block meaningful action by pushing a years-long campaign aimed at sowing doubt among the American public about whether global climate disruption is real or whether it is caused by human activities.

While the Obama Administration has publicly committed to completing these rules as expeditiously as possible, the efforts by industry groups and their conservative allies to make the EPA’s national performance standards for fossil-fueled power plants controversial appears to be having some effect. For example, the Obama Administration just agreed to extend the already abnormally long comment period for the rule on existing power plants by an additional 45 days. The Administration claims that despite this delay it still expects to complete the rule by its self-imposed deadline of June 2015.[xix] It remains to be seen whether the Administration’s claim will hold true.

What Should the Rules Do?

For future power plants, the EPA should issue a rule that sets ambitious limits on greenhouse gas emissions for coal- and natural gas-fired power plants, respectively. The EPA’s proposal would restrict coal-fired power plants’ emissions to 1100 pounds of carbon dioxide per megawatt-hour and gas-fired power plants to 1000 pounds per megawatt-hour. The standard for gas-fired plants should be stronger, though; in the final rule, the EPA should lower the limit to no more than 800 pounds per megawatt-hour.

For existing power plants, the EPA is developing a program under the Clean Air Act that would require states to develop implementation plans for meeting emissions targets, each of which are tailored to the state’s unique circumstances. The program would grant states significant flexibility in designing their implementation plans, such as developing cap-and-trade programs with fellow states and relying on “outside the fence” approaches for cutting emissions including energy efficiency programs and switching to renewable energy sources. This flexibility will ensure that states’ implementation plans are cost-effective and feasible. As proposed, the EPA’s program for existing power plants seeks to cut their greenhouse gas emission by 30 percent below 2005 emissions levels by the year 2030. Given all the flexibility the program would afford to states, the EPA should finalize a rule that sets even more ambitious reduction targets, though. For example, an analysis by the Natural Resources Defense Council finds that a rule similar to the EPA’s proposal could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 35 percent below 2005 emissions levels by 2020 without imposing excessive costs.[xx] In addition, the final rule should maintain ambitious interim targets leading up to the year 2030 to ensure that the states’ plans are making adequate progress.

What’s Next?

Update: In August—a few months behind schedule—the EPA released the final future power plants rule and the final existing power plants rule, along with its proposed federal implementation plan. (Once finalized, the federal implementation plan will be available for the EPA to use for those states that fail to submit an adequate state implementation plan, and it will provide guidance to states to help them design their own state implementation plans.)

In both cases, the agency instituted several changes for both final rules from what was originally proposed. For the future power plants rule, the EPA weakened somewhat the maximum pollution level for future coal-fired power plants to 1400 pounds of carbon dioxide per megawatt-hour—though, this level appears to still be low enough to require some degree of partial carbon capture and sequestration. The EPA made several key changes to the final existing power plants rule. First, it strengthened the rule’s overall goal, calling for a 32-percent reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 as compared to 2005 emission levels. Second, the agency eliminated demand-side energy efficiency as one of the rule’s original four building blocks, though states would still be free to use demand-side energy efficiency as a compliance option. Third, the final rule recalculates most states’ individual greenhouse gas reduction goals, generally assigning greater greenhouse gas reduction obligations for states that have historically done little to reduce their emission and easing the obligations for states that have already made significant progress on decarbonizing their power sector. Fourth, and perhaps most significantly for implementation, the final rule delays states’ obligation to submit a final implementation plan by two years to September 2018. In effect, this change will punt key implementation steps to the next presidential administration.

Once the final rules are published in the Federal Register, industry groups and conservative states opposed to the rules will likely challenge them in court. One key early issue is whether the reviewing court will stay implementation of the rules until all of the legal challenges have been resolved—a process that would take several years. If a stay is granted, this would serve to delay implementation even further, increasing the likelihood that the rules could be blocked by a future presidential administration or Congress that is hostile to action on climate change. The advantage of the change in the final existing power plant rule to delay submission of state implementation plans by two years is that it reduces the likelihood that a stay would be granted. In addition, the rules are under threat from conservative members of Congress, who are considering a variety of legislative measures—including appropriations riders, standalone bills, and Congressional Review Act resolutions of disapproval—aimed at blocking this rule.

For a comprehensive examination of the rules and future implementation issues, see CPR’s August 2015 Issue Alert The Clean Power Plan: Issues to Watch.

Update 2: Following publication of the final rule for existing power plants, industry groups and anti-clean energy states wasted little time in bringing a court challenge. The Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, which has jurisdiction over the case, rejected the industries groups’ and states’ request to stay the rule, but instead set an expedited schedule for hearing the challenge. In a highly extraordinary and unprecedented move, the rule’s challengers sought a stay request at the U.S. Supreme Court. To the shock of nearly all observers, the Court, by a politically-divided 5-4 vote, granted the stay request without explanation, potentially setting a dangerous precedent for premature interventions by the Supreme Court in future cases involving judicial challenges of regulations. Following the Court’s decision, legal observers have debated what significance it holds for a final decision on the rule’s merits. Many predict that the D.C. Circuit will uphold much if not all of the rule for existing power plants, given that the panel there is seen as favorable to environmental issues. In contrast, they predict that the conservative majority in the U.S. Supreme Court would spell doom for the final rule. The recent unexpected death of Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia, viewed by many as a likely foe of the rule once its reached the Court for review, has once again thrown into doubt the future of the EPA’s regulation to control limit carbon dioxide emissions from existing power plants.

The Essential 13: Preventive Controls for Processed Food:

What's at Stake?

From frozen meals and spices to nut butters and cheeses, processed foods are a nearly ubiquitous part of the American diet. They also account for a growing number of foodborne illness outbreaks, which in today’s modern industrialized food system can be breathtaking in scale and devastating in impact. In early 2013, for example, various Farm Rich frozen products infected with a virulent strain of E. coli, sickened at least 35 people across 19 states. In all, about 10 million products, including the company’s Mozzarella Bites and Mini Quesadillas, were recalled in response to the outbreak. Roughly 300,000 pounds of the recalled products had been purchased by schools, and the overwhelming majority of those affected by the tainted food were children.[i] More recently, Listeria-tainted cheese products produced by Roos Foods led to at least one death while causing at least seven reported cases of illnesses, including three cases in infants.[ii] The number of people actually harmed in these and other food illness outbreaks is likely much larger as the vast majority of cases often go undiagnosed or unreported. The Centers for Disease Control, for instance, estimate that for every reported case of Salmonella poisoning, another 38 go unreported.[iii]

The most infamous food illness outbreak related to processed foods in recent years was the massive Salmonella outbreak caused by peanut butter and peanut paste products manufactured by the now-defunct Peanut Corporation of America. Throughout 2007 and 2008, the company—then among the largest peanut-processing plants in the country—began shipping out products it knew were contaminated with Salmonella.[iv] These shipments triggered a 48-state outbreak, killing nine people and sickening at least 714 others, half of whom were children.[v] The outbreak led to the largest food recall in U.S. history, involving hundreds of companies and thousands of products.[vi] Following the outbreak, federal food safety investigators found deplorable conditions at the Peanut Corporation of America’s processing plants, including leaking roofs, widespread mold contamination, standing water, and even dead rodents. It was well known among many industry insiders that these conditions had existed at the company’s facilities for decades.[vii] Since then, top executives from Peanut Corporation of America, including the owner Stewart Parnell, have been convicted of various federal crimes for their role in the outbreak.[viii]

Beyond the immediate health impacts, outbreaks can be economically damaging for the entire industry involved. For example, companies that sourced peanut products from the Peanut Corporation of America had to undertake costly recalls of their own. The owner of one small business estimated that her company suffered around $1 million in losses related to the recall.[ix] Even companies that were not involved suffered substantial losses, as many consumers were scared off from buying all brands of peanut butter, resulting in decreased sales of roughly 25 percent.[x]

Bacteria and other pathogens are not the only threats posed by processed foods; the processing system also introduces the risk of contaminating foods with common allergens such as dairy products, tree nuts, or peanuts. Typically, food items that contain these common allergens must carry a label declaring their presence, so that individuals with allergies can avoid becoming unwittingly exposed. Processed foods that have been accidentally contaminated with these allergens would likely lack such a label, which could endanger the health of individuals with allergies. In fact, the presence of so-called “undeclared” allergens arising from the manufacturing process has become the most common reason for initiating recalls of processed foods—and the health risks they pose can be severe.[xi] According to one Food and Drug Administration (FDA) study, 520 recalls were undertaken between 2005 and 2010 due to undeclared allergens; roughly 10 to 15 percent of the victims of the tainted food experienced anaphylaxis, the most severe—and potentially fatal—form of allergic reaction.[xii]

Processed animal foods can also be a dangerous source of outbreaks, endangering not only the animals that consume the foods but also the humans that live or work with them. In 2012, for example, Diamond Pets Foods initiated a large recall of its products that had been contaminated by Salmonella during the manufacturing process. Several dogs became ill or died as a result, and at least 14 people were also sickened through contact with the food or the infected dogs.[xiii]

To better address these risks, the FDA is working on separate preventive controls rules for the manufacture of processed human and animal foods. These two rulemakings are part of the agency’s efforts to implement the 2011 Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), a law designed to overhaul the U.S. food safety system so that it focuses on preventing foodborne illness rather than reacting to outbreaks after they have already begun.

What’s the Holdup?

The FDA’s development of preventive controls for human and animal foods is already years behind schedule. The FSMA mandated that the FDA issue its final rule on preventive controls for human food no later than July 2012; for the preventive controls for animal food, the FDA was supposed to have issued a proposed rule by October 2011 and the final rule within nine months of the end of the comment period on the proposal. The agency blew past all of these deadlines. The proposal for human food was not issued until January 2013 and the proposal for animal food was not issued until October 2013. Since then, the FDA has fallen even further behind schedule, announcing in December 2013 that it would undertake the unusual step of issuing re-proposals to address some of the early comments it received on the initial proposals.[xiv] The agency only recently issued those re-proposals, in September 2014.[xv] Rather than go through the unnecessary delay caused by issuing these re-proposals, the agency should have simply incorporated any relevant changes made in response to the public comments as it developed the final rules.

Industry opposition has contributed to the FDA’s slow development of the initial proposals as well as the later decision to re-propose each of the preventive controls rules. While at the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA)—where the initial proposals languished for well over a year, causing the FDA to miss a statutory deadline—White House economists significantly weakened both rules by removing several key monitoring and training requirements. Since then, powerful industry trade groups, including the Grocery Manufacturers Association and the Food Marketing Institute, have sought to prevent the FDA from fixing those holes as it worked toward a final rule.[xvi] The trade associations’ efforts have apparently succeeded, as the agency has dedicated much of the re-proposals to addressing their arguments and justifying its ability to reinstate the provisions excised by OIRA.

What Should the Rules Do?

The rules will require covered food processors to develop and implement a Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls (HARPC) system. The HARPC system is, in essence, self-regulation because food manufacturers are responsible for identifying the potential hazards in their processes and then implementing controls to minimize or prevent those hazards. The FDA’s role is limited to reviewing some companies’ HARPC plans to ensure they meet basic standards. This kind of self-regulation is risky, but many food safety advocates consider its proactive and preventive approach an improvement over the current system, which is almost entirely reactive to outbreaks.

Combined, the initial proposals and later re-proposals offer a good start on improving the safety of processed human and animal foods as compared to the status quo, but they can be strengthened in important ways. The rules should require that processors develop HARPC systems that employ the best available methods for preventing food-safety hazards—including those related to pathogens and allergens—that are justified by current science and that address the risks presented by their operations. The controls rule for human foods should be amended to require: reviews of consumer complaints; environmental monitoring for pathogens reasonably likely to occur; finished product testing; supplier approval and verification programs; and reviews of the records associated with these activities. The FDA should also narrow the exemptions in the rules. For human foods, only processors with less than $250,000 in annual sales should be exempt from the requirement to develop HARPC plans. For animal foods, only processors with less than $500,000 in annual sales should be exempt. As drafted, the proposals’ current exemptions allow room for unnecessary exposures to risk from companies that can afford safe procedures.

The rules will also seek to modernize the current good manufacturing practices (CGMP) regulations that apply to processed human foods, while extending these CGMP requirements to animal food processors for the first time. The CGMP requirements can be strengthened by establishing additional requirements covering basic sanitation and training.

What’s Next?

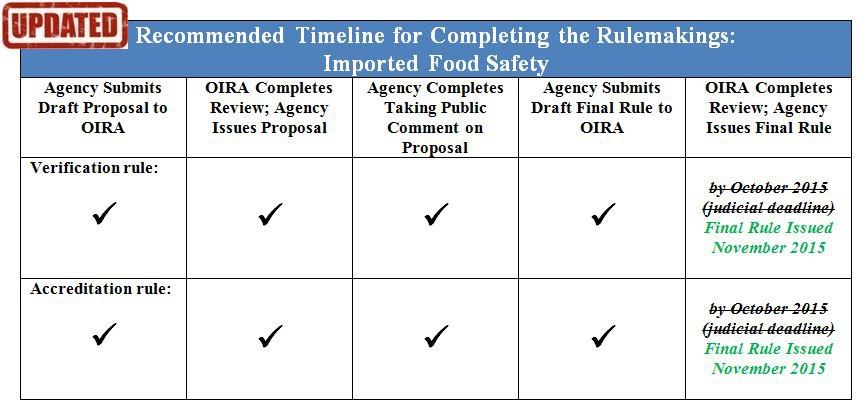

Update: In November 2015, following years of delay, the FDA published its final Foreign Supplier Verification Program and Accreditation of Third Parties rules in the Federal Register. The agency was under a court-ordered deadline to complete the rule by October 2015, which was set after the FDA had failed to issue the rules according to the statutory deadlines.

For both rules, the final versions largely tracked what the FDA had set out in the supplemental proposals. Together, they establish what amounts to a complex system of self-regulation for foreign-based food producers that import products to the United States. Generally speaking, systems of self-regulation rarely inspire much confidence. But, compared to the current approach—which is basically to do nothing—these new rules still represent a huge advance. And with more and more of the food on U.S. tables and store shelves coming from abroad, they are now more important than ever. As with the other rules that make up the FDA’s new food safety program, the ultimate success of its new regulations addressing imported food safety will largely turn on whether Congress sees fit to provide the FDA with adequate resources to perform robust oversight of both the importers and the third-party auditors to ensure effective compliance. In the short- to medium-term, it appears unlikely that such resources will be made available.

The Essential 13: Produce Safety

What's at Stake?

In late summer 2011, Michelle Wakley went into labor three months before her due date. She had eaten a cantaloupe tainted with Listeria and fallen ill. Her newborn daughter Kendall, weighing in at just 3 pounds, 11 ounces, and suffering from a related infection, lived in an incubator for weeks and had to be fed through a stomach tube for more than a year. Kendall may face lifelong physical and mental disabilities. Michelle and Kendall were, in a sense, among the lucky ones. At least 33 people died after eating dirty cantaloupes traced back to the same company: Jensen Farms of Holly, Colorado. The outbreak also sickened 147 people in 28 different states. It was one of the most widespread outbreaks in history and followed closely on the heels of several other major food safety disasters involving contaminated produce, including separate incidents caused by tainted spinach and jalapeño peppers.

The cumulative impact of foodborne illness is difficult to measure because only the most severe cases lead to hospital visits and get reported to government agencies capable of tracking the big picture. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC)—the main and best source of information, given its role in tracking and investigating major outbreaks—estimate that foodborne disease causes 48 million illnesses each year in the United States.[i] Such widespread suffering is reason enough to demand improvements to food safety systems, but the costs to industry are also worth mentioning. Following the 2006 E. coli outbreak in bagged spinach, which sickened more than 200 people in 26 states and killed three others, researchers observed a massive decline in spinach sales across the country, resulting in millions of dollars of losses for innocent producers.[ii]

Congress passed the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) in 2011 in an effort to improve food safety regulations. Under the new law, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was tasked with developing a host of new rules—and to accomplish the task on a short timeline. The combination of two of the rules that Congress specified—the “Produce Safety” rule and the “Preventive Controls for Human Foods” rule—will likely have the biggest impact on foodborne illness outbreaks. The preventive controls rule applies only to non-farm activities such as turning carrots into “baby carrots” or slicing and bagging apples. The Produce Safety rule identifies key farming practices (irrigation, fertilization using manure and biosolids, equipment choice, worker training) that are vulnerable to pathogenic contamination if not carried out properly.

What’s the Holdup?

The Produce Safety rule has been a long time coming. After President Obama signed the law into effect in January 2011, the FDA got to work on the required rules, completed the proposal, and sent the drafts to the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) for review by Thanksgiving of that year. Even though such reviews are generally required to last no longer than four months, the proposals sat there in limbo for more than a year, likely victims of the 2012 elections. Following a lawsuit by public interest advocates aimed at breaking the rules free from White House review, the FDA published the Produce Safety rule for public comment in January 2013. The FDA later extended the public comment deadline three times and hastily organized a series of stakeholder meetings to hear out concerned farmers and food safety advocates. Such backpedaling not only shows a lack of confidence in the rulemaking package as it was published, but also gives opponents extra time to organize a broad base of advocates who can leverage congressional allies and the media to further delay the rulemaking process. The FDA even published a “supplemental” proposal in September 2014, which introduced significant changes to the original proposal. By the time the comment period on the supplemental NPRM closes in December 2014, the Produce Safety Rule will have been out for comment for nearly two years—far longer than usual for most other public health rules.

The farm lobby, channeling the fierce independence of many farmers and the anti-regulatory bent of Big Ag, has cloaked its objections to the Produce Safety rule largely in histrionics. Writing in Food Safety News, for instance, the owner of a seed company in California declared the Produce Safety rule (and the companion Preventive Controls and Foreign Supplier Verification regulations proposed by the FDA) to be a “War on Farmers.”[iii]

From the farm lobby’s and food safety advocates’ perspectives, the four critical issues are the types of crops and farming activities covered by the rule, available exemptions to the rule, the proposed testing standards for irrigation water, and the provisions governing the use of manure and other “biological soil amendments.”

On the water and soil front, the FDA’s goal is to ensure that the irrigation water and manure used to nurture produce do not contaminate the food supply with bacteria such as E. coli and Salmonella, the leading causes of foodborne illness. In the FDA’s estimation, the best way to do that is to test the water regularly (treating the water or delaying harvest if it is too contaminated) and to establish waiting periods between manure application and harvest.

The coverage questions are more complex. A common concern is whether a farmer should be subject to more stringent rules because she occasionally takes produce from neighbors and packages it with her own in order to meet the demands of wholesalers, restaurants, and other “mid-stream” customers. Such post-harvest activities present real risks of spreading contamination, but the FDA is reluctant to apply the same rules to small farmers as it does to major agroprocessors. Another issue is how the FDA should implement the “Tester Amendment,” which exempts certain small farmers from the rules if their total sales fall below a $500,000 per year threshold and a majority of their sales are made directly to consumers or local restaurants or other retail food establishments.

What Should the Rule Do?

The recently published supplemental proposal needs improvement. For example, with regard to the rule’s coverage, the FDA retained the exemption for food “rarely consumed raw.” That exemption allows farmers to use lax practices on such items such as kale and figs, which are frequently consumed raw.[iv] Moreover, it puts the burden on consumers to eliminate pathogens, rather than promoting good agricultural practices. The FDA should simply eliminate this exemption.

On the soil amendments issue, the agency has abandoned its proposed nine-month waiting period between raw manure application and produce harvest. Instead, the FDA proposes to conduct additional and “extensive” research to determine an appropriate risk-based waiting period. And in the meantime, the FDA has given tacit approval for farmers to utilize the waiting periods set forth in the Department of Agriculture’s National Organic Program standards. Those changes make sense. But in the final rule the FDA should also ban the use of sewage sludge in produce-farming operations covered by the rule, given the many contaminants that pass through public sewage treatment plants (e.g., PBDE flame retardants, pharmaceuticals, heavy metals, and other toxins).[v]

The FDA’s proposal strikes a fair balance on irrigation water testing, minimizing contamination risks posed by domestic and wild animals, cleaning tools and other materials, worker training, and procedures for implementing the Tester Amendment. However, recordkeeping rules could be improved by requiring farmers to keep track of which packers and processors handle their produce when those activities occur off the farm.

What’s Next?

Update: The FDA published the final Produce Safety rule in the Federal Register in November 2015. In doing so, the agency satisfied a court-ordered deadline, which was set in response to the agency’s ongoing delays in completing the rule. The final version maintains much of what was included in the agency’s supplemental proposal. One potentially concerning change in the final rule is that the FDA appears to have weakened quality and testing standards for irrigation water that is often a source of pathogenic contamination in produce. On the plus side, the final rule eliminates some of the exemptions that the proposal contained for certain kinds of produce, including Brussels sprouts and bok choy. As with the FDA’s final rules setting Preventive Controls standards for processed human and animal foods, the success of the Produce Safety rule will largely turn on how effectively the agency is able to ensure meaningful compliance with the rule’s requirements. Given Congress’s consistent refusal to provide the FDA with adequate funding for its food safety program implementation, the agency will likely be hampered in its efforts to enforce the rule and instead will have to rely on continued industry self-policing.

The Essential 13: Imported Food Safety

What's at Stake?

About 15 percent of the food consumed in the United States is imported. Imports make up 91 percent of our seafood, 60 percent of our fruits and vegetables, and 61 percent of our honey. Many of these imported foods come from countries that lack effective health and safety regulation. For example, Chinese food producers have been caught spraying cabbage with formaldehyde and trying to sell baby formula tainted with the mercury, a potent neurotoxin.[i] Yet, that country still supplies approximately 50 percent of our apple juice, 80 percent of our tilapia, and 31 percent of our garlic. Vietnamese farmers have been caught sending shrimp to the United States packed in ice made from bacteria-infested water.[ii] Many farm owners in Mexico provide their workers with only filthy bathrooms and no place to wash their hands before gathering such produce as onions or grape tomatoes for export.[iii]

Despite the obvious risks of adulteration and contamination, the resource-strapped Food and Drug Administration (FDA) inspected only 2 percent of food imports and just 0.4 percent of foreign food facilities in 2011. Meanwhile, import-related outbreaks—such as the 84 people sickened by Salmonella-infected Mexican cucumbers in 2013—have become even more frequent.[iv]

The foodborne pathogens that make it to our tables pose a significant threat to children, the elderly, and those with compromised immune systems. The tragic story of 67-year-old Raul Rivera is a case in point. In 2008, after undergoing chemotherapy and radiation, he was told by his oncologist that he would likely survive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Rivera celebrated the positive prognosis by taking his family out for dinner. During the meal, he ate a salsa made with jalapeños, which were later discovered to have been imported from a Mexican farm that had used Salmonella-tainted water for irrigation. He died two weeks later, not of cancer but of salmonellosis.[v]

In part to address this growing threat of contaminated food imports, Congress passed the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). Congress sought to overhaul the U.S. food safety system to focus on preventing foodborne illness outbreaks rather than reacting to them after the fact. The law directs the FDA to issue two key regulations to improve the safety of imported foods: the Foreign Supplier Verification Program and the Accreditation of Third Parties to Conduct Food Safety Audits. The first rule would require food importers to verify that their foreign suppliers have adequate measures in place to prevent adulteration and contamination, while the second would create an independent auditing system through which foreign food facilities could become “certified” as complying with U.S. food safety standards.

What’s the Holdup?

The FSMA instructed the FDA to issue the final Foreign Supplier Verification Program and the Accreditation of Third Parties rules by January 2012 and July 2012, respectively, yet both rules are still a long ways from completion. Despite these deadlines, the FDA failed to issue even the proposals for the rules until July 2013, a full year after they were supposed to be finalized. To make matters worse, the FDA issued in September 2014 a revised proposal of the Foreign Supplier Verification Program rule.[vi] The FDA appears to be treating the two as companion rules, so this revised proposal step will likely result in significant additional delays for the Accreditation of Third Parties rule as well as the Foreign Supplier Verification Program rule.

Interference from economists and political operatives at the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) helped to delay the FDA’s issuance of the initial proposals. The Foreign Supplier Verification Program rule languished at the White House for 20 months, and the Accreditation of Third Parties rule for eight months—both well beyond the maximum four months allowed for OIRA reviews of rules.[vii] Remarkably, OIRA refused to release the rules even after the statutory deadlines for the FDA to issue the final rules had long since passed, causing the agency to violate the clear commands of the FSMA.

What Should the Rules Do?

The FDA should require U.S. companies that purchase food products made overseas to ensure that the foreign suppliers have adequate measures in place to prevent adulteration and contamination. Specifically, the Foreign Supplier Verification rule should direct those companies to inspect foreign supplier facilities, periodically test their shipments, and evaluate their written safety plans. Any company that imports food without an adequate verification program in place should face penalties.

The revised proposal appears to have strengthened many key provisions of the rule, including requiring a more comprehensive analysis of the potential risks posed by imported foods. Some of the provisions in the revised proposal would actually weaken protections as compared to the original proposal, so they should be fixed in the final rule. For example, the revised proposal no longer requires food importers to conduct on-site audits of its foreign suppliers of certain kinds of high-risk foods. (The FDA has yet to assemble a definitive list of foods that fall into this category, but the list will include any foods that pose known safety risks and that are likely to result in severe foodborne illness due to contamination.) Instead, importers would have broad discretion on whether to perform these audits. In the final rule, the FDA should restore the original requirement for conducting on-site audits so that it is mandatory in all cases involving high-hazard foods. The revised proposal also exempts too many “very small importers” and “very small foreign suppliers” because it only applies to firms with annual sales exceeding $1 million. The final rule should only exempt truly small firms, using a cut-off of $500,000 or less.

To be effective, the Accreditation of Third Parties rule should include strict, enforceable standards by which third-party auditors would be judged. Under the rule, foreign food suppliers would hire auditors to inspect their facilities and operations and certify that the suppliers are taking certain minimum steps to ensure the safety of their foods. These certifications would play a key role in the FDA’s new approach to imported food safety under the FSMA: (1) food from certified facilities will qualify for expedited entry into the United States; (2) the FDA may require high-risk foods to be certified before importation; and (3) the FDA will use third-party audit reports to decide which facilities to inspect or which foods to test at the border. Under its proposal, the FDA would also recognize certain accreditation bodies that would give a seal of approval to the private firms, individuals, and government bodies that will serve as foreign-based food safety auditors. In addition to strict standards for evaluating auditors, the Accreditation rules will also need to provide for ongoing and rigorous oversight of both the accrediting bodies and the third-party auditors to ensure that the auditing process does not degrade into a “rubber stamp” for certifying foreign food suppliers.

What’s Next?

The FDA originally proposed the Foreign Supplier Verification Program and Accreditation of Third Parties rules in July 2013. The comment period for those proposals ended in January 2014. More recently, in September 2014, the FDA issued its revised proposal for the Foreign Supplier Verification Program and the comment period for that continues through December 2014. At that point, the FDA will then work toward developing the final versions of both rules, which it is under a judicial order to complete by no later than October 2015.[viii] Considering that the rules would be more than two years past their statutory deadlines at that point, the FDA should not allow the timeline for completing these crucial safeguards to slip any more. Any further delays will only increase the already high costs—measured in premature deaths, debilitating illnesses, and wasted money—that have already accrued as a result of not having an effective regulatory program in place to address the risks posed by dangerous food imports.

The Essential 13: Silica Standard

What's at Stake?

Silica dust is a slow, silent killer. Workers who cut concrete, brick, or tile, who put the finishing touches on drywall, or who mine sand or attend to fracking operations inhale its tiny crystalline particles throughout the day. Roughly 2 million U.S. workers in dozens of different industries toil in workplaces with silica levels high enough to threaten their health. As the dust swirls through workers’ lungs, it causes lung tissue to swell and become inflamed. Workers experience difficulty breathing and, over time, develop scarring and stiffening of the lungs. The resulting condition, called silicosis, is debilitating, and the lung damage that comes with it can increase a person’s risk of tuberculosis and lung cancer. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) estimates that thousands of workers die every year because of silica exposures that are within current legal limits.[i]

Those limits were set more than 40 years ago and were deemed inadequate almost immediately thereafter. Since 1974, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), a government research agency with no regulatory authority, has urged OSHA, which does have regulatory authority, to lower the permissible exposure limit (PEL) for silica by roughly one-half. In September 2013, after decades of research and 17 years of administrative wrangling, OSHA proposed to do just that. The proposal would update OSHA’s outdated exposure limits for crystalline silica with a comprehensive rule that would require employers to limit their workers’ exposure to silica dust and provide other protections including exposure monitoring and free medical exams when workers are exposed to dangerous levels of the dust. Now it us up to President Obama to ensure that the final rule is published quickly.

What’s the Holdup?

OSHA’s efforts to update its silica standards have dragged on for so long largely because of a ponderous culture among rulemaking staff, who engage in excessively thoroughgoing economic and technical analysis. That culture is an overreaction to Supreme Court decisions and Executive Order requirements. Much of OSHA’s scientific and economic research on silica was complete by February 2011, when OSHA sent its draft proposal to the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) for Executive Order 12866 review. Even though reviews are supposed to last no longer than four months, the proposal languished there for more than two and a half years, a striking delay for a rule that is expected to save thousands of lives each year.

OSHA finally got clearance from the White House and published the proposed new silica standards in September 2013. Since then, workers’ advocates have been pressing OSHA to strengthen its proposal, while industry lobbyists have expressed everything from qualified support to outright hostility. In the past year, OSHA has opened the docket for four months of public comment, hosted a three-week hearing at which any interested party could present testimony and cross-examine other parties, and re-opened the docket for another four months of public comment.

OSHA has endured withering criticism throughout the rulemaking process from the usual suspects in the business community—the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, National Association of Homebuilders, American Chemistry Council, and the Construction Industry Safety Coalition—all of whom complain about the costs of the rule while denying its clear benefits to workers. Even the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Office of Advocacy, which despite its SBA affiliation has increasingly acted at the behest of big industry, weighed in to encourage further delay in publishing the rule.

Industry groups have also been working their connections in Congress in hopes of further delaying the rule. After OSHA released the rule in late 2013, industry lobbyists rallied 70 Members of Congress (54 on the House side and 16 Senators) to sign letters to OSHA demanding additional delays in the rulemaking process. As OSHA gets closer to publishing a final rule, the affected industries will no doubt turn to their congressional allies again to pressure the agency. Such high-level political pressure is best answered by the White House, so President Obama should intervene to keep the agency’s deliberations on track.

What Should the Rule Do?

OSHA’s proposal is close to what silica-exposed workers need. It goes well beyond the current protections, which are limited to an inadequate PEL and basic protections afforded by other generic standards. Instead, the new rule establishes a strong PEL (50 micrograms per cubic meter) and backs it up with specific requirements about exposure monitoring, employee training, medical surveillance, and eliminating silica exposures through engineering and work-practice controls rather than respirators and facemasks.

OSHA should still do a few things to strengthen the rule. First, the rule needs medical removal protection for workers. When workers are exposed to dangerous levels of silica dust and show signs of potential chronic injury, they should be given the option of taking jobs that are less hazardous, without loss of pay or seniority. OSHA has required such accommodations in numerous rules governing workers’ exposures to other toxic chemicals.

The rule’s medical surveillance requirements should also be expanded. As is required in other OSHA health standards, employers should be required to make medical surveillance (e.g., exams, x-rays, etc.) available to workers at an “action level” set at one-half of the PEL (i.e., 25 micrograms per cubic meter).

OSHA should also clarify that host employers and staffing agencies are jointly liable for training and other protections. Companies often hire workers on a temporary or “contingent” basis so that they can shift workers’ compensation premiums, payroll taxes, unemployment insurance, and other costs to another employer. If OSHA clarifies that both host employers and the staffing agencies they use to hire workers are jointly liable for compliance with silica regulations, workers will be better protected.

What’s Next?

The docket for the silica proposal closed on August 18, 2014, nearly a year after the proposal finally left OIRA. OSHA is in the process of reviewing comments, the hearing transcript, and new evidence submitted to the record during the 11 months of open debate on the proposal. To the dismay of worker advocates, OSHA has a history of stalled rulemakings at this stage in the process. For instance, two rules waiting in limbo right now are:

- Confined spaces in construction – record closed October 2008;[ii] and,

- Slip/trip/fall prevention – hearing ended January 2011.[iii]

Having the sad distinction of being the only agency that ever lost a rule to Congressional Review Act “veto”—its comprehensive plan to reduce ergonomic injuries in the workplace—OSHA should be far more focused on getting the silica rule finished in time than its ponderous approach to the rulemaking process indicates. Accordingly, OSHA needs to complete its review of the docket and send the draft final rule to OIRA as soon as possible. For its part, the Obama Administration should ensure that OIRA completes its review of the draft final rule within the period spelled out in the executive order granting it authority to review—four months, at most.

The Essential 13: National Ozone Pollution Standard

What's at Stake?

Clean Air Act regulations to limit dangerous ground-level ozone pollution rank among this country’s most successful environmental policies. These rules help prevent around 4,300 premature deaths, 86,000 emergency room visits, and 3.2 million lost school days every year.[i] The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that by 2020 these rules will deliver even greater benefits, helping prevent as many as 7,000 premature deaths, 120,000 emergency room visits, and 5.4 million lost school days every year. Ozone pollution-control rules have also strengthened the U.S. economy by promoting the health of the agriculture and forestry sectors. The EPA estimates that in 2010 the rules prevented $5.5 billion worth of crops and forest products being lost to ozone-related damage; by 2020, the EPA predicts that they will annually prevent losses of crops and forest products worth $10.7 billion.

But more can and should be done. According to the American Lung Association, nearly half of all Americans—more than 140 million people in all—continue to live in areas with harmful levels of ozone pollution.[ii] A 2011 analysis by the Natural Resources Defense Council found that U.S. communities had issued more than 2,000 Code Orange and Code Red ozone alerts in just the first seven months of that year alone.[iii] The poor and racial minorities are disproportionately harmed since the highest pollution levels are typically found in urban and economically distressed communities. For example, a 2012 study by the Connecticut Department of Public Health found that asthma-related hospitalization rates were roughly twice as high for the state’s most urban areas as compared to their neighboring suburbs, which the report in part attributes to disparities in relative air quality.[iv] Rising temperatures brought about by global climate disruption threaten to make matters even worse. In a recent study, the National Center for Atmospheric Research projects that climate disruption-related impacts could cause the number of unhealthy ozone pollution level days to increase 70 percent by 2050.[v]

To further protect people and the environment, the EPA should strengthen the ozone National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS). A NAAQS is a regulatory program under the Clean Air Act that sets maximum allowable levels for common air pollutants that are necessary for safeguarding even the most vulnerable people—such as the elderly and those with poor health—as well as the environment. The law requires the EPA to review each pollutant’s NAAQS, including the one for ozone, at least once every five years and lower it if new science shows that the existing limits are not adequately protecting people and the environment. Numerous scientific studies show that even very low levels of ozone—measured in parts per billions (ppb) of the air we breathe—can trigger asthma attacks and aggravate lung diseases such as bronchitis, leading to missed work and school days, emergency room visits, and even death. Scientists have known for a long time that the current NAAQS for ozone of 75 ppb, which was set in 2008, is far too weak. Instead, the EPA’s elite Clean Air Science Advisory Committee (CASAC) recommends that the NAAQS should be set as low as 60 ppb. The EPA has estimated that restricting ozone pollution to this level would annually prevent up to up to 12,000 premature deaths, 5,300 nonfatal heart attacks, 58,000 cases of aggravated asthma, and 2.5 million missed school and work days.[vi]

What’s the Holdup?

The oil and gas industry, manufacturers, and the business community in general have launched a full-scale assault against the EPA’s efforts to update the ozone NAAQS, prompting the agency to develop the rule at an unduly slow pace. Corporate interests have sought to make the rule controversial by spreading bogus claims about its economic impacts. For example, the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) paid for a highly flawed study that purports to find that the rule will harm the economy and costs jobs, though the study’s grossly inflated estimates bear little relationship to reality.[vii] Industry allies in Congress, such as Sen. David Vitter (R-La.), have similarly sought to exaggerate the rule’s impacts.[viii] Over the years, such dire predictions have been as predictable as they are wrong. Every time that the EPA has sought to strengthen the ozone NAAQS in the past, opponents of strong clean air rules have made such outlandish claims, but the predicted economic disruption and massive job losses have never come to pass.[ix] In addition to attacking the rule’s costs, industry groups have also attempted to sow doubt about the rule’s benefits, sponsoring studies that purport to find that low levels of ozone pollution do not cause premature deaths or have any other adverse health impacts.[x]

Corporate interests successfully deployed these attacks the last time that the EPA sought to strengthen the ozone NAAQS in 2011. Industry lobbyists even scored a meeting with high-ranking White House officials and, according to media accounts, persuaded them that the rules would have severe negative economic impacts in states that would be vital to President Obama’s fast-approaching reelection campaign.[xi] Less than two months after the meeting, the White House ordered the EPA to postpone its efforts to update the ozone NAAQS.[xii]

The ozone NAAQS update is also facing stiff resistance from anti-regulatory Members of Congress. In September, members of the Senate and the House of Representatives separately introduced companion legislation to block the EPA from finalizing the rule until most of the country has come into compliance with the current 75-ppb standard. The bill would also require the EPA to ignore public health and science and instead set future ozone NAAQS based on whether industry compliance with a more protective standard would be “feasible.”[xiii]

What Should the Rule Do?

The EPA should settle for nothing less than a NAAQS set at 60 ppb. This standard is necessary to meet the Clean Air Act’s requirement that the ozone NAAQS be set at a level “requisite to protect the public health” with “an adequate margin of safety.” The U.S. Supreme Court held in 2001 that the law requires the standard be based on public health considerations only, and that forbids the EPA is prohibited from considering costs. Consistent with this requirement, CASAC—a group of independent experts formed to advise the EPA on scientific matters related to its clean air regulations—unanimously recommended in June 2014 that the agency significantly revise the NAAQS downward to within the range of 60 to 70 ppb. Based on its review of the most up-to-date science on ozone’s harmful health effects, CASAC further advised that the EPA set the standard toward the lower end of its recommended range, noting that “the recommended lower bound of 60 ppb would certainly offer more public health protection than levels of 70 ppb or 65 ppb and would provide an adequate margin of safety.” In August, EPA staff echoed CASAC’s recommendations in its final Policy Assessment report, providing further support for a NAAQS set at 60 ppb. The EPA should also follow CASAC’s advice in setting a unique “secondary” NAAQS necessary for protecting plants and trees.

What’s Next?

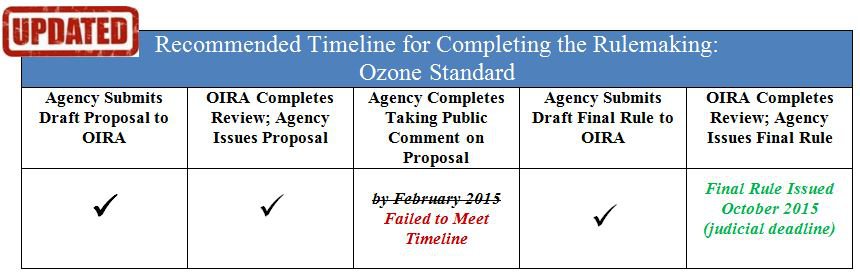

Update: In October 2015, the EPA issued its final rule setting the ozone NAAQS at 70 ppb—the least protective level it considered in its proposal. In doing so, the agency appears to have bowed to political and industry pressure, rather than heeding the advice of its science advisors to set the standard at no greater than 60 ppb. If it survives judicial review, this final rule will likely go down as one of the Obama Administration’s greatest missed opportunities when it comes to promoting public health and environmental protection.

The final rule now faces competing challenges in the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. Several conservative states and industry groups have filed suits arguing that the EPA erred in not keeping the standard at the current level of 75 ppb. Several environmental groups have challenged the rule as violating the Clean Air Act, because it is not sufficiently protective of public health and the environment.

Separately, the final rule is likely to remain a target of legislation by the Republican-controlled Congress in the coming year. Members have introduced various bills in both chambers that would either block or delay the rule outright, or that would result in weaker ozone NAAQS in the future by forcing the agency to prioritize industry profits ahead of public health and environmental concerns when setting new standards. Congress may attempt to move one or of these bills this year, but it is unlikely that President Obama would sign off on them or that Congress would be able to override a veto. Antiregulatory members also tried but failed to include riders in last year’s appropriations bill for the EPA that would prohibit the agency from enforcing the new ozone NAAQS. These members may attempt to push a similar rider as part of this year’s appropriations process.

The Essential 13: Waters of the United States

What's at Stake?

The United States lost a total of more than 62,000 acres of coastal wetlands between 2004 and 2009.[i] The state of Louisiana alone loses an area of wetland the size of a football field every hour.[ii] In total, the lower 48 states have lost roughly half of the 220 million acres of wetlands estimated to have been in existence in the 1600s, before the introduction of modern industry and agriculture.[iii]

Wetlands are crucial for both humans and the environment, controlling flooding, filtering pollutants from water, and serving as important habitat and breeding grounds for aquatic species. More than one-third of U.S. endangered or threatened species live exclusively in wetlands, and nearly half of all such species inhabit or use wetlands at some point in their lives.[iv] Fish and shellfish that inhabit or use U.S. wetlands make up 75 percent of the country’s total commercial seafood harvest and have an estimated annual value of $15 billion.[v]

Streams, tributaries, and many other kinds of more isolated waters are also disappearing or suffering degradation at alarming rates, thanks to increasing activities related to agriculture, construction, and extractive industries. Similar to wetlands, these water bodies supply unique habitat to a variety of animals and plants—including endangered species and economically valuable migratory birds—and they are essential to maintaining the health of the larger rivers and lakes to which they are connected. In particular, these water bodies serve as important conduits of nutrient non-point source pollution that now is among the leading threats to water quality in these larger rivers and lakes.

The consequences of destroying wetlands and these other more isolated water bodies can be catastrophic. For example, this past summer, a large toxic algal bloom in Lake Erie contaminated public drinking water supplies in Toledo, Ohio, leaving nearly a half-million area residents without access to potable water for several days. The algae, a growing layer of which covers Lake Erie every summer, is the result of rising water temperatures and the massive influx of nutrient pollution runoff, much of it in the form of fertilizer and manure from the surrounding farms and livestock feeding operations. Nutrient non-point source pollution is causing similar problems in other larger water bodies throughout the United States, including the large algal blooms that afflict the Chesapeake Bay and the massive dead zone that forms in the Gulf of Mexico each year.[vi]

A recent series of muddled U.S. Supreme Court decisions has spawned widespread confusion over whether the Clean Water Act’s protections now cover many of these wetlands and more isolated water bodies. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (the Corps) have been attempting to clarify this confusion ever since. A 2007 congressional oversight memorandum concluded that because of this ongoing confusion “[h]undreds of violations have not been pursued with enforcement actions and dozens of existing enforcement cases have become informal responses, have had civil penalties reduced, and have experienced significant delays.”[vii] Without a clear definition of whether several common categories of water bodies are covered by the Clean Water Act, EPA regional offices must now assess these waters on a case-by-case basis, which wastes the agency’s scarce personnel and financial resources and undermines the effectiveness of its Clean Water Act enforcement program.

To address this confusion, the EPA and the Corps have launched a joint rulemaking that attempts to establish a clear regulatory definition that, consistent with both the previous court decisions and the best available science, delineates which water systems are covered by the Clean Water Act. In general, the rule seeks to reduce the categories of waters that must be assessed on a case-by-case basis by identifying and defining those categories that are always covered by the Clean Water Act and those that are never covered.

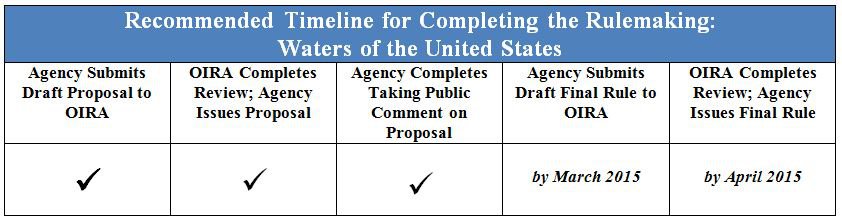

What’s the Holdup?